AMḤAYDA (TRIMITHIS)

| Arabic | أمحيدة |

| Greek | Τριμιθις |

| English | Amheida | Amhida | Amhada |

| DEChriM ID | 10 |

| Trismegistos GeoID | 2733 |

| Pleiades ID | 776235 | PAThs ID | 174 |

| Ancient name | Trimithis |

| Modern name | Amḥayda |

| Latitude | 25.668709 |

| Longitude | 28.873704 |

| Date from | -820 |

| Date to | 365 |

| Typology | Town |

| Dating criteria | - |

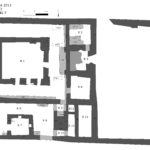

| Description | Amḥayda, Dakhleh Oasis Project site no. 33/390-L9-1, is understood to be the Roman city of Trimithis. Preliminary surveys were conducted from 2000-2002, and excavations were initiated by Columbia University in 2004, directed by Roger Bagnall. Columbia University is still a continuing partner, but New York University is now the primary sponsoring institution, collaborating with other participating groups in the Dakhleh Oasis Project. Excavations of the site show occupation from at least the Old Kingdom up to the fourth century CE. There are a number of different excavation areas, with the main areas of focus being those designated 1, 2 and 4. Area 1 Area 2 Sub-area 2.2 The Roman thermae, probably consisting of 10 rooms, is located north of B1 and B5; it has been designated as B6. There appears to have been a number of building/utilisation phases of the thermae, with it being understood that B6 represents the latest stage (this needs to be clarified). The architecture of the thermae indicates that it dates to the Roman Imperial Period. Graffiti found on the northern wall of R25 dates to 325 or later. There is limited evidence to date the destruction phase, but it is likely that the thermae were undergoing modifications in the 4th century. These restorations/modifications were abandoned for some reason, as is indicated by the thousands of prepared but unused mosaic tesserae found in R30, which also explains the lack of objects found in the building. These tesserae are significant in that they prove the existence of mosaic floors in Trimithis and can be “considered the first proof for mosaic floors in the oases of the western desert” (Bagnall et al. 2012: 3). The baked bricks and some walls of the thermae were then used in the construction of B1 and B5, as mentioned above, (the row of rooms south of the central room 24 in particular has extensive parts – walls and floors – reused from the bath). There is evidence of a building phase predating the thermae, identified below the floors, consisting of bread ovens. Sub-area 2.3 The focus of this area is B7, located east of sub-area 2.2, which is believed to have been a funerary church structure. The building is oriented on an East-West axis, and contains within its perimeter at least 8 burials, 4 of which have been studied. These interred individuals are positioned on their backs with their heads to the west, looking east. There is no evidence of coffins, biers or grave goods in these four graves. However, in some of them remains of textiles were found, suggesting the bodies were wrapped in funerary shrouds. Plant remains, tentatively identified as rosemary and myrtle bundles, were also discovered in a number of these burials. There were at least two floor levels, with a subterranean room which has been interpreted as a crypt. The eastern wall of room 1, the main room, has a number of Greek inscriptions, one of which reads hos theos. According to ceramic evidence, the building has been dated to the fourth century. Features in a number of rooms indicate that the space, or parts of it, was used as a food preparation area in its post-abandonment phase. Area 4 In the Roman period, a new temple was built under the emperor Titus. This was followed by the latest construction phase during the reign of emperor Domitian, which stood to the north of the chapel decorated under Titus, wherein several older buildings within the enclosure were demolished and their stone blocks reused in the construction of a larger sanctuary, with that of Titus being incorporated entirely into this new temple (built or decorated during the latter half of the second century CE). This final temple construction then went through two distinct destruction phases, one of which quarried away the Roman temple, leaving only the lowest courses of stonework. We see uses of these stones throughout other excavated structures in Amḥayda, including B6. Sub-area 4.1 As well as hundreds of these construction blocks, excavation in Area 4.1 uncovered a number of pits. Although differing in shape, depth and dimension, they can be said to be round, oval or elongated, with almost all of them cutting into one another, indicating that they were dug at different times. One of these pits (F90) included a coin hoard of 850 tetradrachms divided into three textile bags, dating from Claudius to Marcus Aurelius. Pottery fragments found in the filling of these pits dates from the Old Kingdom until the fourth century CE. Some of these pits also contained temple blocks, most of which are related to the Saite temple dedicated to the god Thoth (which were reused in the Roman period after the building was dismantled). The fact that the concentration of these blocks varies between pits enables speculation regarding the original layout of the Roman temple, with it being understood that many come from the external N-S running wall of the temple. Roughly at the centre of AR50 appears the only portion left undisturbed by the cutting of these pits; the area seems to be delimited by walls, possibly creating a room; five complete pottery coffins, and the traces of two broken ones, in situ, as well as numerous fragments of similar coffins attest to the area being used as an animal cemetery with a presumably sacred function. This interpretation is aided by the discovery of 25 fragments of bronze Osiris statuettes and pendants as well as a large depositional cluster of at least 40 miniature vessels (DSU 120). There are also numerous indicators of bread baking, namely bread molds and grinding stones, as well as ash pockets. The general area is incredibly disturbed with recognisable vessels from the Old Kingdom to Islamic periods. Sub-area 4.2 This area is located to the north of 4.1 and consists of a number of stone foundation blocks. While the function of these structures is difficult to interpret, they include a number of inscriptions dating to the Roman period; at least 5 instances of individuals having signed their name and patronymic on the top of a block, 4/5 were of the same individual, Petosiris son of Tithoes, and the 5th was Petenephotes son of Petosiris. Perhaps a structure of significance is a building situated on a hill east of the temple area, which is characteristed by a sort of peristyle oriented east-west, the plan of which is very similar to that of the large East Church at Kellis. |

| Archaeological research | Preliminary surveys were conducted between 2000 and 2002, and excavations were initiated by Columbia University in 2004, directed by Roger Bagnall. Columbia University is still a continuing partner, but New York University is now the primary sponsoring institution as of 2008, collaborating with other participating groups in the Dakhleh Oasis Project (DOP). |

• Aravecchia, N. 2015. “Christianity at Trimithis and in the Dakhla Oasis.” In An Oasis City, edited by R. S. Bagnall, N. Aravecchia, R. Cribiore, P. Davoli, O. E. Kaper and S. McFadden, 119-148. New York: NYU Press.

• Aravecchia, N., T. L. Dupras, D. Dzierzbicka and L. Williams. 2015. “The Church at Amheida (Ancient Trimithis) in the Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt. A Bioarchaeological Perspective on an Early Christian Mortuary Complex.” Bioarchaeology of the Near East 9: 21–43.

• Ast, R. and R. S. Bagnall. 2015. “New Evidence for the Roman Garrison of Trimithis.” Tyche 30: 1–4 (pl. 1-3).

• Ast, R. and P. Davoli. 2016. “Ostraka and Stratigraphy at Amheida (Dakhla Oasis, Egypt): A Methodological issue.” In Proceedings of the 27th International Congress of Papyrology Warsaw, 29 July – 3 August 2013, edited by T. Derda, A. Łajtar, J. Urbanik, 1447-1471. Warsaw: The Journal of Juristic Papyrology, Supplements XXVIII.

• Bagnall, R. S. 2013. Eine Wüstenstadt: Leben und Kultur in einer Ägyptischen Oase im 4. Jahrhundert n. Chr. Stuttgart: Steiner Franz Verlag.

• Bagnall, R. S. 2015. “Other Evidence of Christianity at Amheida.” In An Oasis City, edited by R. S. Bagnall, N. Aravecchia, R. Cribiore, P. Davoli, O. E. Kaper, and S. McFadden, 131-35. New York: ISAW/NYU Press.

• Bagnall, R. S., N. Aravecchia, R. Cribiore, P. Davoli, O. E. Kaper and S. McFadden. 2015. An Oasis City. New York: NYU Press & ISAW.

• Bagnall, R. S., R. Ast, R. Cribiore and C. Caputo. 2017. Amheida III. Ostraka from Trimithis, Volume 2: Greek Texts from the 2008-2013 Seasons. New York: NYU Press & ISAW.

• Bagnall, R. S and R. Cribiore. 2012. “Christianity on Thoth's Hill." In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R.S. Bagnall, P. Davoli, C.A. Hope, 409-415. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

• Bagnall, R. S and P. Davoli, eds. 2007. “Amhida.” In Report to the Supreme Council of Antiquities, on the 2005-2006 Season Activities of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by J. Mills, 35-62.

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. Field Report on the 2000 and 2001 Seasons at Amheida. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2001.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. Excavations at Amheida, 2002. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2002.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. Excavations at Amheida, 2004. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2004.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. Excavations at Ahmeida, 2005. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2005.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. Excavations at Amheida, 2006. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2006.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. Dakhleh Oasis Project Columbia University, Excavations at Amheida 2007. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2007.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. Dakhleh Oasis Project Columbia University, Excavations at Amheida 2008. Accessed April 12, 2020. Preliminary Report. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2008.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. Dakhleh Oasis Project New York University Excavations at Amheida, Report 2009. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2009.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. New York University Excavations at Amheida 2010 Preliminary Report. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2010.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. New York University Excavations at Amheida 2011 Preliminary Report. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2011.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. University of Reading Excavations at Amheida Preliminary Report 2012. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2012_Reading.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. New York University Excavations at Amheida 2012 Preliminary Report. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2012.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. University of Reading Excavations at Amheida Preliminary Report 2013. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2013_Reading.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. New York University Amheida/Trimithis 2013 Seasons Report, Directed by Roger S. Bagnall. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2013.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. New York University Amheida/Trimithis 2014 Season Report, Directed by Roger S. Bagnall. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2014.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S. and P. Davoli et. al. New York University Amheida/Trimithis 2015 Season Report, Directed by Roger S. Bagnall. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.amheida.org/inc/pdf/Report2015.pdf

• Bagnall, R. S., P. Davoli, Olaf E. Kaper and Helen Whitehouse. 2006. “Roman Amheida: Excavating a Town in Egypt's Dakhleh Oasis.” Minerva 17/6: 26-29.

• Bagnall, R. S., McFadden, S., and Boleman. E. 2016. “Wall paintings in the Late Roman city of Trimithis (Amheida), Dakhla Oasis: Preliminary Survey.” Bulletin of the American Research Center in Egypt 208: 1-8.

• Bagnall, R. S. and G. R. Ruffini. 2004. “Civic life in Fourth Century Trimithis. Two Ostraca from the 2004 Excavations.” Zeitschrift fur Papyrologie und Epigraphik 149: 143-152.

• Bagnall, R. S. and G. R. Ruffini. 2012. Amheida I. Ostraka from Trimithis, Volume 1: Texts from the 2004-2007 Seasons. New York: NYU Press & ISAW.

• Boozer, A. L. 2005. “In Search of Lost Memories: Domestic Spheres and Identities in Roman Amheida, Egypt.” Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy Working Papers Series 05-07: 1-28.

• Boozer, A. L. 2007. “Housing Empire: The Archaeology of Daily Life in Roman Amheida, Egypt.” PhD Thesis, Department of Anthropology. New York, Columbia University.

• Boozer, A. L. 2010. “Memory and Microhistory of an Empire: Domestic Contexts in Roman Amheida, Egypt.” In Archaeology and Memory, edited by D. Boric, 138-157. Oxford: Oxbow.

• Boozer, A. L. 2011. “Forgetting to Remember in the Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt.” In Cultural Memory and Identity in Ancient Societies, edited by M. Bommas, 109-126. London, New York: Continuum.

• Boozer, A. L. 2012. "Globalizing Mediterranean Identities: The Overlapping Spheres of Egyptian, Greek and Roman Worlds at Trimithis.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 25: 93-116.

• Boozer, A. L. 2013a. “The Archaeology of Amheida (Egypt).” In The Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by Claire Smith. Springer.

• Boozer, A. L. 2013b. “Archaeology on Egypt's Edge: Archaeological Research in the Dakhleh Oasis, 1819-1977.” Ancient West and East 12: 117-156.

• Boozer, A. L. 2013c. “Frontiers and Borderlands in Imperial Perspectives: Exploring Rome's Egyptian Frontier.” American Journal of Archaeology 117: 275-292.

• Boozer, A. L. 2014. “Urban Change at Late Roman Trimithis (Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt).” In Egypt in the First Millennium AD: Perspectives from New Fieldwork, edited by Elisabeth O’Connell, 23-42. Leuven: Peeters.

• Boozer, Anna L. 2015. Amheida II: A Late Romano-Egyptian House in the Dakhla Oasis: Amheida House B2. With contributions from D. V. Campana, A. Cervi, P. J. Crabtree, P. Davoli, D. Dixneuf, D. Ratzan, G. Ruffini, U. Thanheiser, and J. Walter. New York: NYU Press & ISAW.

• Bravard, J.-P., A. Mostafa, P. Davoli. K. A. Adelsberger, P. Ballet, R. Garcier, L. Calcagnile and G. Quarta. 2016. “Construction and Deflation of Irrigation Souls from Pharaonic to Roman Period at Amheida (Trimithis), Dakhla Oasis, Egypt Western Desert.” Géomorphologie. Relief, Processus, Environment 22/3: 305-24.

• Caputo, C. 2014. “Amheida/Trimithis (Dakhla Oasis): Results from a Pottery Survey in Area 11.” Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 24: 163-177.

• Caputo, C. 2016. “Ceramic Fabrics and Shapes.” In Amheida III: Ostraka from Trimithis, Volume II: Greek Texts from 2008-2013 Seasons, edited by R. Ast and R. S. Bagnall: 62-88. New York: New York University Press.

• Caputo, C., J. Marchand., and I. Soto. 2017. “Pottery from the 4th-Century House of Serenos in Trimithis/Amheida (Dakhla Oasis).” In LRCW 5: Late Roman Coarse Wares, Cooking Wares and Amphorae in the Mediterranean: Archaeology and Archaeometry, Alexandria (Egypt), 6-10 April 2014, edited by D. Dixneuf, Études Alexandrines 43, vol. 2: 1011-26. Alexandria.

• Caracuta, V., G. Fiorentino, P. Davoli and R. Bagnall. 2018. “Farming and Trade in Amheida/Trimithis (Dakhelh Oasis, Egypt): New Insights from Archaeobotanical Analysis.” In Plants and People in the African Past: Progress in African Archaeobotany, edited by A. M. Mercuri, A. C. D’Andrea, R. Fornaciari and A. Höhn, 57-75. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

• Crabtree, P. J., and D. V. Campana. 2015. “Faunal Remains from Amheida Area 1.” In A Late-Romano-Egyptian House in the Dakhla Oasis: Amheida House B2. Amheida II, edited by A. L. Boozer, 369-73. New York: New York University Press.

• Crabtree, P. J., and D. V. Campana. 2016. “Class and ‘Romanization’ in Late Roman Egypt: Issues of Identity and Faunal Remains from the Site of Amheida in the Dakleh Oasis, Western Egypt.” In Bones and Identity: Zooarchaeological Approaches to Reconstructing Social and Cultural Landscapes in Southwest Asia, edited by N. Marom, R. Yeshuran, L. Weissbrod and G. Br-Oz, 293-302. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

• Cribiore, R., P. Davoli and D. M. Ratzan. 2008. “A Teacher's Dipinto from Trimithis (Dakhleh Oasis).” Journal of Roman Archaeology 21: 170-191.

• Cribiore, R. and P. Davoli. 2013. “New Literary Texts from Amheida, Ancient Trimithis (Dakhla Oasis, Egypt).” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 187: 1-14.

• Cribiore, R., G. Vittmann, R. S. Bagnall. 2015. “Inscriptions from Tombs at Bir esh-Shaghala”. Chronique d'Égypte 90: 335-349.

• Davoli, P. 2012a. “Reflections on Urbanism in Graeco-Roman Egypt: a Historical and Regional Perspective.” In The Space of the City in Graeco-Roman Egypt: Image and Reality, edited by E. Subías, P. Azara, J. Carruesco, I. Fiz and R. Cuesta, 69-92. Tarragona: Institut Català d'Arqueologia Clàssica.

• Davoli, P. 2012b. “Amheida 2007-2009: New Results from the Excavations.” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli and C. A. Hope, 263-278. Oxford: Oxbow.

• Davoli, P. 2014. “UniSalento nel deserto occidentale egiziano: Dieci anni nell'Oasi di Dakhla.” Il Bollettino dell'Università del Salento IV/5: 23-26.

• Davoli, P. 2017. “A New Public Bath in Trimithis (Amheida, Dakhla Oasis)”. In Collective Baths in Egypt 2. Recent Discoveries and Perspectives, edited by B. Redon, 193-220. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

• Davoli, P. Amheida 2004-2006: New Results from the Excavations. Accessed April 13, 2020. https://isaw.nyu.edu/research/amheida/inc/unpublished/davoli_2006-pdf

• Davoli, P., with contributions by R. S. Bagnall, O. E. Kaper. 2006. “I Romani nel Deserto.” Pharaon, September, 2006.

• Davoli, P. and R. Cribiore. 2010. “Una scuola di greco del IV secolo d.C. a Trimithis (Oasi di Dakhla, Egitto).” Atene e Roma: 73-87.

• Davoli, P. and O. E. Kaper. 2006. “A New Temple for Thoth in the Dakhleh Oasis.” Egyptian Archaeology 28:12-14.

• Dixneuf, D. 2015. “La Céramique de la Maison B2 à Amheida (Oasis de Dakhla).” In Amheida II. A Late Romano-Egyptian House in the Dakhla Oasis: Amheida House B2, edited by A. L. Boozer, 201-80. New York.

• Ghica, V. 2012. “Pour une histoire du christianisme dans le désert Occidental d’Égypte.” Journal des Savants 2: 189-280.

• Ghica, V. 2016. “Vecteurs de la christianisation de l’Egypte au IVe siècle à la lumière des sources archéologiques.” In Acta XVI Congressus Internationalis Archaeologiae Christianae, Rome 22-28.9.2013, edited by Olof Brandt and Gabriele Castiglia, 199, 241, 248 and fig. 9e. Città del Vaticano: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana.

• Kaper, O. E. 2009. “Epigraphic Evidence from the Dakhleh Oasis in the Libyan Period.” In The Libyan Period in Egypt, Historical and Cultural Studies into the 21st - 24th Dynasties: Proceedings of a Conference at Leiden University, 25-27 October 2007, edited by G. P. F. Broekman, R. J. Demarée and O. E. Kaper. 149-159. Leuven: Peeters.

• Kaper, O. E. 2010. “A Kemyt Ostracon from Amheida, Dakhleh Oasis.” Bulletin de l'Institut français archéologie orientale 110: 115-126.

• Kaper, O. E. 2011. “Tempel an der "Rückseite der Oase: Aktuelle Grabungen decken eine ganze Kultlandschaft auf.” Antike Welt 2: 15-19.

• Kaper, O. E. 2012. “Epigraphic Evidence from the Dakhleh Oasis in the Late Period.” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli and C. A. Hope, 167-176. Oxford: Oxbow.

• Kaper, O. E. 2015a. “Petubastis IV in the Dakhla Oasis: New Evidence About an Early Rebellion Against Persian Rule and its Suppression in Political Memory.” In Political Memory in and After the Persian Empire, edited by J.M. Silverman and C. Waerzeggers, 135-149. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

• Kaper, O. E. 2015b. “Amheida Before the Romans.” In An Oasis City, edited by R. S. Bagnall, N. Aravecchia, R. Cribiore, P. Davoli, O. E. Kaper and S. McFadden, 35-60. New York: ISAW/NYU Press.

• Kaper, O. E. Forthcoming. “Amheida Between the Old and Middle Kingdoms.” In The Oasis Papers 7. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

• Kaper, O. E. and R. J. Demarée. 2005. “A Donation Stela in the Name of Takeloth III from Amheida, Dakhleh Oasis.” Jaarbericht Ex Oriente Lux 39: 19-37.

• Leahy, L. M. 1980. “The Roman Wall-Paintings from Amheida.” The Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities Journal 10/4: 331-378.

• McFadden, S. 2014. “Art on the Edge: The late Roman Wall Painting of Amheida, Egypt.” In Akten des XI. Internationalen Kolloquiums der AIPMA (Association internationale pour la peinture murale antique), Archäologische Forschungen 23: 359-370.

• McFadden, S. 2016. “Wall Paintings in the Late Roman City of Trimithis (Amheida), Dakhla Oasis: a Tantalizing Prelminary Survey.” Bulletin of the American Research Center in Egypt 208: 3-9.

• Muskens, S. 2009. “Een Romeinse stad in de Egyptische Woestijn. Recent Veldwerk in Amheida, Dachla Oase.” Ta-Mery 2: 7-12.

• Pyke, G. 2005. "Amheida Pottery Report 2005." Unpublished.

• Schulz, D. 2010. “De Villa van Serenus – een Reconstructive.” Monumenten 31/6 (June).

• Schulz, D. 2011. “Die neue Villa des Serenus: Rekonstruktionsarbeiten in der Wüste.” Antike Welt 2: 20-23.

• Schulz, D. 2015. “Colours in the Oasis: the Villa of Serenos.” Egyptian Archaeology 46: 23-26.

• Silver, C. S. 2012. “Painted Surfaces on Mud Plaster and Three-Dimensional Mud Elements: The Status of Conservation Treatments and Recommendations for Continuing Research.” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli and C. A. Hope, 337-347. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

• Vittmann, G. 2017. “An Abnormal Hieratic Letter from Dakhleh Oasis (Ostracon Amheida 16003)." In A True Scribe of Abydos. Essays on First Millennium Egypt in Honour of Anthony Leahy, edited by C. Jurman, B. Bader and D. A. Aston, 491-503. Leuven: Peeters.

• Wagner, G. 1987. Les oasis d’Égypte à l’époque grecque, romaine et byzantine d’après les documents grecs: Recherches de papyrologie et d’épigraphie grecques. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Warner, N. 2012. “Amheida: Architectural Conservation and Site Development, 2004-2009.” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli and C. A. Hope, 363-379. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Json data

Json data