ABŪ ṢĪR (TAPOSIRIS MEGALĒ)

| Greek | Ταποσιρις |

| Latin | Tapostri |

| Arabic | أبو صير |

| English | Abusir |

| French | Abousir |

| DEChriM ID | 56 |

| Trismegistos GeoID | 2260 |

| Pleiades ID | 727241 | PAThs ID | 338 |

| Ancient name | Taposiris Megalē |

| Modern name | Abū Ṣīr |

| Latitude | 30.946185 |

| Longitude | 29.518716 |

| Date from | - |

| Date to | - |

| Typology | City |

| Dating criteria | - |

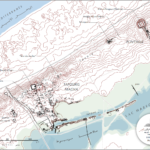

| Description | Taposiris Megalē, modern-day Abū Ṣīr, is located some 45km from Alexandria. The site has long-since been identified with ancient Taposiris Magna, with the connection distinctly demonstrated via an inscription found by E. Breccia, which comprises a dedication to Isis made by the priests of Taposiris (Breccia 1906: 145-149; id 1907: 97-98; id 1922: 338; Boussac 2007: 445). This is accompanied by additional indicators, such as papyrus fragments from Oxyrhynchos, uncovered by Grenfell and Hunt, referring to Isidos Taposiriados, ‘Isis of Taposiris’ (P.Oxy. 1454, 11-12), and a dedicatory inscription to ‘Lady Isis of Taposiris’ (CIL XI. 1544 = EDR 102706) uncovered from an ancient temple at Faesulae (near Florence). The ancient township was of a considerable size, expanding for many kilometers to the east and west, and comprised a vast temple complex, a tower-structure, various funerary, residential and industrial areas, including a port, and multiple baths. Having had an extensive period of occupation, the topography of the site is expectedly sophisticated, and only a minute amount of the total surface of the site has been systematically explored (Betrò 1982: 56). It is believed that the city was founded by Ptolemy II between 280 and 270BC, as ascertained by his cartouche found during the Hungarian excavations (Vörös 2004: 46). The acropolis has been attributed to this early phase, though no real architectural studies of the temple or enclosure have been published (Vörös 2003: 296; id 2004: 12; Boussac 2007: 449). As of yet, the material evidence attests to a second century BCE foundation date (Boussac 2007: 450). Considering its size, the French mission, who have conducted the most extensive work to date, have divided Taposiris Megalē into two main areas, those of the ‘Upper’ and ‘Lower’ towns. The ‘Upper Town’ (or ‘Breccia District’, given that it was the area excavated by E. Breccia) comprises the temple enclosure/fort and the terrace to the south, which includes the animal necropolis, tholos baths and a number of additional structures (including a villa with decorative floor mosaics), all of which is organised either side of the north-south running road that connected the temple to the port (Breccia 1922: 340; Boussac 2007: 461, 469, 472). Also identified in the area are a system of underground aqueducts just to the east of the temple, running north-south (Breccia 1922: 341; Boussac 2007: 473). This terrace area was densely populated in the Byzantine period (Boussac 2007: 451). To the south, the ‘Lower Town’ comprises the port basin, thermae and buildings predominantly relating to artisanal and commercial activities (Breccia 1922: 344; Boussac 2007: 451, 453; Nenna et al. 2000: 97-112). It seems that the area did not function as a port in the Hellenistic period, but was rather home to a district of shops and warehouses (at least in the western section). The area was then abandoned, perhaps the result of a flood, and the artificial levee was constructed sometime in the second century CE (Boussac 2007: 455, 457). The two ancient structures that dominate the landscape of modern Abū Ṣīr are the temple enclosure/fort and the tower. The latter, standing some 17 meters high, is situated to the east of the temple enclosure/fort. Interpretations of this structure vary. Given that it is not only in the middle of a funerary area, but that it is situated immediately above a large rock-cut mortuary complex, it has been interpreted as a funerary monument (Adriani 1952: 139). H. Thiersch, however, considered it to have been a lighthouse, and thus the closest chronological relation to the Lighthouse of Alexandria (Thiersch 1909: 26-30; Breccia 1922: 343). The common understanding regarding the temple enclosure was that it was an unfinished construction, which never housed a temple. This derived from the mistaken belief that the enclosure walls were contemporaneous with the floor level of the acropolis, thus implying that, considering there were no architectural traces of a temple, that no temple was ever constructed (Vörös 2004: 46). This prevailing notion meant there was limited interest in the acropolis, with the restoration work of Adriani and Binton in the mid-20th century completely ignoring the potential for exploration in the area. Breccia, nonetheless, assumed that there had been a temple here that was dedicated to Osiris (Breccia 1922: 337). The Hungarian mission, working between 1998 and 2004, revealed that, in reality, a Hellenic shrine with Doric columns had indeed stood here, with the existing floor being a later addition dating to the Roman period (Vörös 2004: 47). Material remnants, including cultic statues and sacred vessels, revealed that this temple was built to honour Isis (Vörös 2004: 48-49, 128-131). This material corresponds to a number of lamps uncovered by Breccia, which were also host to depictions of the goddess, and the aforementioned attestations of the cult at Taposiris (Vörös 2004: 136). When the enclosure was re-occupied by the Roman military, the sanctuary and any additional structures were dismantled down to their foundation stones, with various architectural elements added to the enclosure walls and used in the construction of barrack-like structures (Breccia 1922: 340; Vörös 2004: 59, 66). The Christian occupation of the site is documented both architecturally and through written sources. The earliest attestation of a Christian community dates from the third century during the persecution of Decius in the letters of Sergios (Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. VI 40/4; Grossmann 1992: 25, n. 1). As of yet, the architectural indicators are limited to three churches: a contra-apse church in the town area (Grossmann 1992; id 2002: 384, pl. 4), a church situated extra muros in the western foreland, interpreted as perhaps having been a charitable institution (Grossmann 1982: 152-154 and fig. 11; id 2002: 385-387, pl. 5) and a church situated in the temple enclosure/fort, towards the eastern entrance (Grossmann 2002, pl. 3 and 185). Only this latter structure is datable from the fourth century (Grossmann 2002: 381; Betrò 1982: 51). There is an additional structure which was identified by the American team as a church dating to the fourth century ('Area A'), situated at the western end of the ancient lakebed (Ochsenschlager 1976: 276, fig. 1; id 1979: 504, fig. 2). Grossmann does not consider this is a church, however, but a Roman villa, predominantly because the ‘apse’ faces south (Grossmann 1992: 27 n. 6). Additional elements of Christianity have been identified, such as numerous marble slabs with engraved crosses reused as floor paving in various areas of the site (Adriani 1952: 132, fig. 68; Vörös 2004: 138-139, 146-147; Boussac and Redon 2017: 62, fig. 12). Two construction phases of the church in the temple enclosure/fort are identifiable, the first of which is architecurally situated in the fourth century, contemporaneous with the construction of a number of rooms/cells along the interior of the enclosure walls, with the secondary phase perhaps occurring in the fifth century (Grossmann 2002: 383). These structures, and thus the church, have been interpreted in light of two diverging arguments: (1) the structures are the result of the transformation of the temple enclosure into a military barracks/fort, with the church constructed to accommodate the soldiers, (2) the rooms lining the inside of the enclosure walls are connected to a supposed monastic occupation of the site and were intended to house the monks. The later argument can be seen in Ward-Perkins article from 1946, in which he references the History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria, written by the late-tenth century writer Severus Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ, who, in relaying the account of the death of a seventh century patriarch, makes reference to the monastery of Taposiris (Evetts 1907: 26; Ward-Perkins 1946: 48, 51). Ward-Perkins suggested that perhaps the monastic occupation was far earlier than the seventh century, however, with De Cosson proposing that the establishment of this monastery was contemporaneous with the destruction of pagan shrines in Alexandria (De Cosson 1935: 110). Grossmann disputes this, arguing in favour of it only having been a military camp (Grossmann 2002, p. 381). Despite Grossmann’s rejection of the classification, the monastic interpretation was also championed by the Hungarian team, who believed that, as well as housing military forces in a secondary phase of occupation, the temple enclosure came to house a monastic community in a third occupation phase (Vörös 2004: 67). The director of the mission, G. Vörös, associated the site with Dayr al-Zuǧāǧ, the ‘Monastery of Glass’ (also known as Ennaton), a monastery tentatively documented from the fourth century, but more probably in operation from the fifth century, said to have been situated in western Alexandria, on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea near Lake Maryūṭ (Vörös 2004: 153). The location of this monastery has long since been a topic of discussion and, despite remaining ambiguous today, the classification was considered appropriate by the excavators due to the discovery of glass furnaces near the southern gate of the temple enclosure/fort (Vörös 2004: 149). Given the reference made in the History of the Patriarchs, it is safe to assume there was indeed a monastic community at Taposiris, at least from the seventh century. But, whether the community was located in the temple enclosure/fort is uncertain. Grossmann casually suggested that the extra muros church could have been a monastery, but this seems equally speculative (Grossmann 1982: 154). Given that Dayr al-Zuǧāǧ was said to have operated into the 15th century and that the latest archaeological levels of the site date to the seventh century, the correlation between this monastery and Taposiris Megalē seems improbable (Boussac 2007: 450; Goehring 2018: 538). |

| Archaeological research | Given the prominent location of the site and the size of the above-ground features, namely the temple enclosure/fort and the tower, the site has long-since been an area of attraction, the temple being denoted by de Cosson as the finest ancient monument north of the pyramids. The temple enclosure/fort and tower were mentioned in the travel accounts of numerous modern figures, including N. Granger, J.-R. Pacho, H. F. Minutoli, B. St. John, H. Thiersch (Granger 1745; Pacho 1827: 6, pl. I, pl. II 2; Minutoli 1825: 41; St. John 1849; Thiersch 1909). Napoleon’s savants also visited in 1801, and made the first surface survey and graphic documentation of the tower and temple enclosure/fort, seemingly without having excavated any areas. But the 5th volume of the Description de l’Égypte only dedicated a single plate to these major monuments. De Cosson gives a concise overview of additional figures who visited Abū Ṣīr as part of larger ventures (De Cosson 1935: 161-175). The first archaeological work to be conducted at the site was that of Evaristo Breccia, the Italian Egyptologist and director of the Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria, in 1906. This was also Breccia’s first excavation. Unfortunately, the work was of a limited scope, only lasting a single season due to difficulties with funding. Despite optimistic announcements made regarding the publication of the excavation report (Breccia 1907: 113; id 1909: 378), then the hope for an overall work on the area of Maryūṭ (Breccia 1924: 284-285), Breccia only published a minute amount of information concerning the work, namely the few pages dedicated to the site included in his Alexandrea ad Aegyptum, published in French in 1914 and English in 1922. Despite not eventuating in the intended publications, Breccia’s unfinished work, comprising the unpublished manuscript for a monograph dedicated to Taposiris and the wider region of Maryūṭ, as well as associated field notes, photographs and drawings, were donated by his wife to the University of Pisa. In 1980-81, Edda Bresciani entrusted these documents to Maria Carmela Betrò, who, in turn, gave them to Hungarian Egyptologist Győző Vörös in 2001, when he was directing excavations at the site (Betrò 1982). In 2002, Vörös and a number of others digitised the whole archive, though it does not seem to be accessible online. The work of Breccia was followed by that of A. Adriani, who became the director of the Greco-Roman Museum after him. Adriani carried out two brief campaigns between 1937 and 1939, which focused predominantly on cleaning the area inside the temple enclosure/fort, and restoration and consolidation work on the tower (Adriani 1952: 130-131; Betrò 1982: 46). This was followed by restoration work directed by Jasper Binton, which occurred 1945-48, though there are no related publications of these field seasons (Vörös 2004: 46). This consolidatory work was followed by that carried out by the SCA and led by R. Nouweir and F. el-Chabouri, although this seems to have focused predominantly on Plinthine (Nouweir 1955: 66-68). An American mission then conducted work on behalf of the Archaeological Research Institute of Brooklyn College, New York and the Brooklyn Museum, directed by Edward L. Ochsenschlager and financed by the Smithsonian Institution. It is not entirely clear how many seasons of work were carried out, but at least one campaign occurred with certainty, between July 7th and August 19th 1975 (Ochsenschlager 1976). Given that Ochsenschlager stated that “full-scale excavations are planned to commence in the near future”, we can perhaps assume that there were issues with funding, resulting in the unexpected cessation of work (Ochsenschlager 1979: 506). This work concentrated on four areas - Areas A (a large building built of local limestone, dated to the fourth cenutry CE, mistakenly considered to have been a church), B, C and presumably D (Ochsenschlager 1976; id 1979; Betrò 1982: 47). Hungarian and French missions instigated work simultaneously in 1998, with the teams each concentrating on different areas of the site. The Hungarian mission, directed by Győző Vörös with team members from various Hungarian institutions (incl. Budapest Technical University Faculty of Architecture, Hungarian Academy of Arts, Hungarian National Museum and the Péter Pázmány Catholic University), conducted work almost exclusively within the perimeter of the temple enclosure/fort, though there were also a number of exploratory test-pits at the perimeter of the complex. The French mission, directed by Marie-Françoise Boussac from 1998 to 2017 and then by Bérangère Redon as of 2018 until the present, has focused on the terrace area south of the temple enclosure/fort and the harbour basin in the lower part of town, an area which has received very limited attention. The mission is also focusing on the Hellenistic necropolis of nearby Plinthine (Boussac 2007: 448). Recently having been supported by the Shelby White and Leon Levy Program for Archaeological Publications, the French mission will publish in the near future a monograph and a web-GIS dedicated to the site, specifically focusing on the history of lake Mareotis in antiquity, examining environmental changes and their impact on the dynamics of societies and the economy. The work of the Hungarian mission did not result in any excavation reports, but was accompanied by two monographs of a chiefly popular nature. The latter work makes reference to plans to restore the church in the temple enclosure/fort, and to transform the area into a monastic/pilgrimage complex. These plans had been endorsed by Shenouda III, the pope of the Coptic Church, in the early 2000s, although it is not clear if they had actually received official permission from the Egyptian government. Nonetheless, they never came to fruition, and the Hungarian mission ceased work in 2004. The following year, the area of the temple enclosure/fort became the concession of a joint Egyptian-Dominican mission consisting of a collaboration between Egyptologist Zahi Hawass and the University of Santo Domingo, under the direction of Kathleen Martinez. The collaboration between the two figures appears to have been brief, with Hawass no longer participating in the mission. Martinez has nonetheless continued work, having conducted some 15 or 16 seasons of ‘excavations’. Martinez is trained as a lawyer and initiated excavations at the site with the sensational hope of finding the location of Cleopatraʼ tomb. Unfortunately, despite the fact that work has been on-going for an extensive period of time, no material has ever been published. Notwithstanding the lack of scientific output, numerous documentary film crews have recorded fieldwork, in which Martinez has on numerous occasions made baseless claims regarding her ‘discoveries’, asserting that she proved the existence of a temple dedicated to Isis, despite the fact that this was already known, and in one appearance claiming that the aqueduct, already identified by Breccia in 1906, was a newly discovered burial chamber. For unknown reasons, the Grand Egyptian Museum inaugurated an exhibition in 2018 dedicated to Martinez’s efforts at Taposiris, titled “10 years of Dominican Archaeology in Egypt”. |

• Adriani, A. 1952. Annuaire du Musée gréco-romaine. Alexandrie, 3 (1940-1950). Alexandria: Imprimerie de la Société de publications égyptiennes S. A. E. pp. 129-159 and pls. 47-52.

• Betrò, M. C. 1982. “Evaristo Breccia inedito.” Egitto e Vicino Oriente 3: 45-62.

• Le Bomin, J. 2016. “Les thermes byzantins de Taposiris Magna. La ce?ramique d’un de?potoir de la fin du VIe et du de?but du VIIe s. apr. J.-C.” Bulletin de la céramique égyptienne 26: 39-72.

• Bouchaud, C. and B. Redon. 2017. “Heating the Greek and Roman Baths in Egypt. Papyrological and Archaeobotanical Data.” In Collective Baths in Egypt 2. New Discoveries and Perspectives, edited by B. Redon, 323-349. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Boussac, M.-F. 2001. “Deux villes en Maréotide: Taposiris Magna et Plinthine.” Bulletin de la Société française d’égyptologie 150: 42-72.

• Boussac, M.-F. 2007. “Recherches récentes à Taposiris Magna et Plinthine, Égypte (1998-2006).” Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 151, 1: 445-479.

• Boussac, M.-F. 2009. “Taposiris Magna: la création du port fermé.” In Archéologie et environnement dans la Méditerranée antique, edited by F. Dumasy and F. Queyrel, 123-142. Geneva: Librairie Droz.

• Boussac, M.-F. 2010. “À propos des divinités de Taposiris Magna à l’epoque hellénistique.” In Paysage et religion en Grèce ancienne. Mélanges offerts à Madeleine Jost, edited by P. Carlier and C. Lerouge-Cohen, 69-74. Paris: De Boccard.

• Boussac, M.-F. 2012. “Rapport de la mission française de Taposiris-Plinthine. Campagne 2012.” Supplément au bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 112: 295-305.

• Boussac, M.-F. 2013. “Rapport de la mission française de Taposiris-Plinthine. Campagne 2013.” Supplément au bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 113: 217-225.

• Boussac, M.-F. 2014. “Rapport de la mission française de Taposiris-Plinthine. Campagne 2014.” Supplément au bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 114: 173-182.

• Boussac, M.-F. 2015a. “Recent Works at Taposiris and Plinthine.” Bulletin de la Société archéologique d’Alexandrie 49: 189-217.

• Boussac, M.-F. 2015b. “Rapport de la mission française de Taposiris-Plinthine. Campagne 2015.” Supplément au Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 115: 201-210.

• Boussac, M.-F. and B. Redon. 2016. “Taposiris Magna et Plinthine.” Supplément au Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 116: 204-225.

• Boussac, M.-F. and B. Redon. 2017. “Taposiris Magna et Plinthine.” Supplément au Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 117: 51-64.

• Boussac, M.-F. et al. 2001. “Taposiris et Plinthine 1999.” Orientalia 70: 351-352.

• Boussac, M.-F. et al. 2003. “Taposiris et Plinthine 2000-2002.” Orientalia 72: 5-7.

• Boussac, M.-F. et al. 2004. “Taposiris et Plinthine 2003-2004.” Orientalia 73: 3-5.

• Boussac, M.-F. et al. 2006. “Taposiris Magna.” Le monde de la Bible 172: 43.

• Boussac, M.-F. et al. 2006. “Taposiris et Plinthine 2005-2006.” Orientalia 75: 192-195.

• Boussac, M.-F. et al. 2007. “Taposiris et Plinthine 2006-2007.” Orientalia 76: 177-179.

• Boussac, M.-F. et al. 2008. “Taposiris et Plinthine 2007-2008.” Orientalia 77, 3: 187-191.

• Boussac, M.-F. et al. 2009. “Taposiris et Plinthine 2008-2009.” Orientalia 78, 2: 127-131.

• Breccia, E. 1906. “Note epigrafiche.” Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 7: 145-149.

• Breccia, E. 1907. “Cronaca del museo e degli scavi e ritrovamenti.” Bulletin de la Société archéologique d’Alexandrie 9: 97-114.

• Breccia, E. 1911. Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes. Iscrizioni greche e latine. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Breccia, E. 1914. Alexandrea ad Aegyptum. Guide de la ville ancienne et moderne et du Musée gréco-romain. Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d’arti grafiche. 123-130.

• Breccia, E. 1922. Alexandrea ad Aegyptum. A Guide to the Ancient and Modern Town, and to its Graeco-Roman Museum. Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d’arti grafiche.

• Caramatti, L. 1994. “Annibale Evaristo breccia. Documenti sugli scavi e sul Museo greco-romano di Alessandria negli archivi eggitologici dell’ateneo pisano.” PhD Dissertation, University of Pisa.

• De Cosson, A. 1935. Maraeotis. Being a Short Account of the History and Ancient Monuments of the North-Western Desert of Egypt and of Lake Mareotis, 109-115. London: Country Life.

• Dhennin, S. 2008. “An Egyptian Animal Necropolis in a Greek Town.” Egyptian Archaeology 33: 12-14.

• Fournet, T. 2011. “Trois curiosités architecturales des bains de Taposiris Magna (Égypte): voûte à crossettes, radiateur et dalle clavée.” Revue Archéologique 52, 2: 323-347.

• Fournet, T. 2012. “Thermes impériaux e monumetaux de Syrie du Sud et du Proche-Orient.” Cahiers de la ville Kérylos 23: 185-246.

• Fournet, T. and B. Redon. 2006. “Un édifice exceptionnel de la chôra alexandrine: les bains souterrains de Taposiris Magna.” Archéologia 439 (December): 52-59.

• Fournet, T. and B. Redon. 2007. “Tell el-Herr, Taposiris Magna et les bains de l’Égypte gréco-romaine.” In Tell el-Herr. Les niveaux hellénistiques et du Haut-Empire, edited by D. Valbelle, 116-127. Paris: Errance.

• Fournet, T. and B. Redon. 2010. “Le bain grec, à l’ombre des thermes romains.” Les dossiers d’archéologie 342: 56-63.

• Fournet, T. and B. Redon. 2013. “Greek Baths’ Heating System: News Evidences from Egypt.” In Greek Baths and Bathing Culture: New Discoveries and Approaches, edited by M. Trümper and S. Lucore, 239-263. Leuven: Peeters.

• Fournet, T. and B. Redon. 2017a. “Bathing in the Shadow of the Pyramids. The Greek Baths in Egypt, an Original Bathing Model.” In Collective Baths in Egypt 2. New Discoveries and Perspectives, edited by B. Redon, 99-137. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Fournet, T. and B. Redon. 2017b. “Catalogues of the Baths of Egypt I. Catalogue of the Greek Tholos Baths of Egypt.” In Collective Baths in Egypt 2. New Discoveries and Perspectives, edited by B. Redon, 389-435. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Fournet, T., S. Lucore, B. Redon and M. Trümper. 2013. “Catalogue of Greek Baths.” In Greek Baths and Bathing Culture: New Discoveries and Approaches, edited by M. Trümper and S. Lucore, 269-333. Leuven: Peeters.

• Granger, N. 1745. Relation du voyage fait en Égypte par le sieur Granger. En l’année 1730. Paris: Jacques Vincent.

• Grossmann, P. 1982. “Ab? M?na. Zehnter vorläufiger Bericht. Kampagnen 1980 und 1981.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen archäologischen Instituts Kairo 38: 152-155 and fig. 11

• Grossmann, P. 1992. “A New Church at Taposiris Magna-Abusir.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie 31: 23-30.

• Grossmann, P. 2002. Christliche Architektur in Ägypten, 381-383. Leiden: Brill.

• Guimer-Sorbets, A.-M. and B. Redon. 2017. “The Floors of the Ptolemaic Baths of Egypt: Between Technique and Aesthetics.” In Collective Baths in Egypt 2. New Discoveries and Perspectives, edited by B. Redon, 140-170. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Minutoli, H. F. 1825. Reise zum Tempel des Jupiter Ammon in der libyschen Wüste und nach Ober-Aegypten in den Jahren 1820-21. Berlin: A. Rucker.

• Nenna, M.-D., M. Picon and M. Vichy. 2000. “Ateliers primaires et secondaires en Égypte à l’époque gréco-romaine.” Travaux de la Maison de l?Orient 33: 97-112.

• Nouweir, R. 1955. “Les fouilles dans la zone d’Abousir.” La revue du Caire 33: 66-68.

• Ochsenschlager, E. L. (Leclant, J). 1976. “Fouilles et travaux en Égypte et au Soudan, 1974-1975.” Orientalia 45: 275-276.

• Ochsenschlager, E. L. (Leclant, J). 1980. “Fouilles et travaux en Égypte et au Soudan, 1978-1979.” Orientalia 49: 347.

• Ochsenschlager, E. L. 1979. “Taposiris Magna. 1975 Season.” In Acts of the First International Congress of Egyptology, Cairo 1976, edited by W. F. Reineke, 503-506 and plates 62-65. Berlin: Verlag.

• Ochsenschlager, E. L. 1999. “Taposiris Magna.” In Encyclopedia of Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, edited by K. A. Bard, 759-761. London, New York: Routledge.

• Pacho, J.-R. 1827. Relation d’un voyage dans la Marmarique et la Cyrénaïque. Paris: Firmin-Didot.

• Redon, B. 2012a. “L’insertion spatiale et économique des établissements balnéaires en Égypte hellénistique et romaine.” In “Quartiers” artisanaux en Grèce ancienne. Une perspective méditerranéenne, edited by G. Sanidas and A. Esposito, 57-80. Lille: Septentrion.

• Redon, B. 2012b. “Établissements balnéaires et présences grecque et romaine en Égypte.” In Grecs et Romains en E?gypte : territoires, espaces de la vie et de la mort, objets du prestige et du quotidien, edited by P. Ballet, 155-170. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Redon, B. 2018. “Taposiris Magna et Plinthine, deux villes de Maréotide.” Supplément au Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 118: 65-80.

• St. John, B. 1849. Adventures in The Libyan Desert and The Oasis of Jupiter Ammon. London: John Murray.

• Thiersch, H. 1909. Pharos. Antike Islam und Occident. Leipzig, Berlin: Druck und Verlag von B. G. Teubner.

• Vörös, G. 2001. Taposiris Magna. Port of Isis. Budapest: Egypt Excavation Society of Hungary.

• Vörös, G. 2004. Taposiris Magna. A Temple Fortress, and Monastery of Egypt. Budapest: Egypt Excavation Society of Hungary.

• Vörös, G. 2010. “The Temple Treasures of Taposiris Magna.” Egyptian Archaeology 36: 15-17.

• Ward-Perkins, J. B. 1946. “The Monastery of Taposiris Magna.” Bulletin de la Société archéologique d?Alexandrie 36: 48-53.

Auxiliary titles

• Evetts, B. trans. 1907. Patrologica orientalis, tome V fasc. I. History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria III. Agatho to Michael I (766). Paris: Firmin-Didot.

• Goehring, J. E. 2018. “Ennaton, Monastery of.” In The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity, Vol. 1, edited by O. Nicholson, 538. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Json data

Json data