AL-ḤAMMĀMIYYA

| Arabic | الحمّامية |

| English | Hamamieh | Hemamieh | el-Hamamiyah |

| French | el-Hamamija | el-Hammamija | el-Hemamiah | el-Hemamija | Hemamije |

| DEChriM ID | 27 |

| Trismegistos GeoID | 56773 |

| Pleiades ID | - | PAThs ID | 147 |

| Ancient name | - |

| Modern name | al-Ḥammāmiyya |

| Latitude | 26.916667 |

| Longitude | 31.483333 |

| Date from | -4400 |

| Date to | 860 |

| Typology | Cemetery |

| Dating criteria | Funerary material, radiocarbon dating, coinage. |

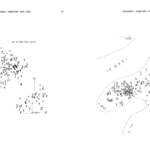

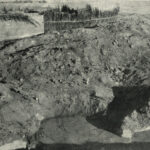

| Description | The site of al-Ḥammāmiyya is situated on the eastern bank of the Nile, opposite Timā, two kilometers north of Dayr al-Naṣārā (Timm, 1984-1992: 1078-1079). It is part of al-Badārī, a toponym covering a large area comprising numerous cemeteries, including those at the sites of Qāw al-Kabīr, al-Badārī, Mustaǧidda, and al-Maṭmar. Al-Ḥammāmiyya, which includes a predynastic settlement as well as a cemetery, is situated between the modern villages of al-Ḥammāmiyya and Šayḫ ʿĪsā (Holmes and Friedman 2014: 108). The archaeological area was limited to the foot of the mountains due to the existence of a modern Muslim cemetery, which has developed around the tomb of Šayḫ ḤāǧīʿĀlī (Paribeni, 1940: 277). Based on the maps provided by the British School of Archaeology in Egypt (BSAE), who excavated the site in the 20s, there are two burial areas separated by a wādī. The cemetery was used in predynastic, early dynastic and Roman times, with the former being the most abundant (Petrie 1924: IX). The site is best known for its predynastic occupation, which has been the main focus of related work (Holmes and Friedman 2014: 117). Two gold coins recovered during the BSAE’s excavations, dating to the reign of the Abbasid caliph al-Mutawakkil, indicate that the site was occupied up to the ninth century (Brunton 1930: 32). There is a Coptic settlement located on the highest part of the spur, which is now reduced to some remnants of mud-brick walls (Paribeni, 1940: 278). Here, Coptic graves are densely packed, dug in the earth, and almost always descending to a depth equal to or greater than the prehistoric burials (Paribeni, 1940: 278). The corpses were predominantly laid supine without specific orientation (Paribeni, 1940: 278). None of these graves show any trace of coffins. A number of the interments included various jewelry items, namely earrings, rings, bracelets and bronze pendants. The most interesting items noted by Roberto Paribeni, who led the first excavations of the area in 1906, were a fragment of a large terracotta plate with a painted figure in military dress holding a spear with two lions at his feet, the composition of which seems to be related to the motif of St. Menas flanked by two camels. An additional item of interest was a small pendant in the shape of an equilateral cross in solid bronze, which, together with a number of beads, formed the necklace of a child. Among the beads from another necklace (in a different grave?) was a small glass scarab (Paribeni, 1940: 279). No images of these objects are included in Paribeniʼ publication, and we have not been able to locate them. Perhaps they are in Museo Egizio in Turin. During the first season of excavations conducted by the BSAE, a Coptic codex containing the Gospel of John was found in a ceramic vessel near point CB on the map, “in the neighbourhood of the Roman or early Coptic graves”, but not actually in a grave (Petrie 1924: IX, Brunton 1930: 31). This has been palaeographically dated to the late fourth century (Thompson 1924: XIII). The codex appears to have been well-used, presumably too worn for private use, leading to the supposition that it must have been for official use in a church (Petrie 1024: X). During fieldwork, traces of mud-brick walls were identified “in the immediate neighbourhood” (of the find-spot) (Petrie 1924: IX). The structure to which these walls belonged was presumed to have been a church. A bronze censer was recovered from a rubbish-dump nearby, supporting the hypothesis of the church. This church, or chapel, is said to have stood between points CE and CF on the map (Brunton 1930: 31). Traces of painted plaster indicate that the walls had been decorated. Additionally, burials of men, women and children were identified underneath the pavement of the building (Brunton 1930: 31). Numerous artefacts of note are mentioned in the publications. However, often it is not specified from which of the sites the object comes. For example, an item will be mentioned with reference to a plate (which includes the grave number), then in the same sentence another item can be referenced, but it is devoid of an accompanying image, and the grave number is not given. The tomb and artefact registers are not immediately clarifying. Noteworthy artefacts that are definitively stated to have come from al-Ḥammāmiyya include the bronze censer mentioned above (Brunton 1930: Pl. X, 3), a scarab with two Coptic crosses and an animal in bronze from grave 1708 (no drawing is provided of this, but there is a description in Brunton 1930: 27), a bronze pendant depicting a mounted figure presumed to be St. George (Brunton 1930: pl. XLVII, 12), and a bone cross (the find-spot of this object is not immediately clear). The Roman period tomb register includes two examples of bone crosses, one of which is from grave 1703, which is presumably the item in question as the other one listed is from grave 5300, which, based on the grave numbers provided, is from a cemetery near al-Badārī (Brunton 1930: pl. XXXIX). Without stratigraphic information, however, these objects cannot be attributed to the fourth century. |

| Archaeological research | Archaeological research of the site has been limited. An Italian team worked here under the direction of Ernesto Schiaparelli in 1906, while Georg Steindorff led further fieldwork on the site in 1914. Limited information is available concerning these excavations. Steindorff mentions the work in a few lines published in the notes and news of the first edition of the JEA, stating that the excavation he directed was part of the Ernst von Sieglin Expedition, working in Egypt and Nubia. Although Steindorff states that he was “keeping a more detailed survey of the scientific results for a later report”, no such report ever seems to have been published. Schiaparelli entrusted the exploration of al-Ḥammāmiyya to Roberto Paribeni, while he waited to begin excavations at Qāw al-Kabīr. The only publication relating to this work, dated to 1940, is considerably brief. The most extensive excavation was conducted by the British School of Archaeology in Egypt, which had seasons in 1923, 1924 and 1925. The work was spread over the area of the whole Qāw/al-Badārī district, however, comprising the sites of Qāw al-Kabīr (modern-day al-ʿAtmāniyya), al-Ḥammāmiyya, and al-Badārī, and the resulting publications are difficult to use. Rather than presenting the material in a site-specific manner, they were organised chronologically: “The first two volumes … deal with the period from the First to the Eleventh Dynasties, and the third with the later periods and the great rock-cut tombs. These volumes are named Qau and Badari, while the fourth, which is confined to the Badarian and other predynastic ages, is called Badari in order to distinguish it easily.” (Brunton 1927: 2). The information is a bit muddled as a result. The origin of material is determinable via the graves number (if given), with numbers 1500 through to 2100 used for al-Ḥammāmiyya (Brunton 1927: 3). As well as a cemetery, the site includes a predynastic settlement, which remains the main focus of the area today. As part of ‘The Prehistory of Badari Project’, one season of excavation was conducted at the site in 1989. |

• Brunton, G. and G. Caton-Thompson 1928. The Badarian civilisation and predynastic remains near Badari. British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account [46] (30th year). London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt, Bernard Quaritch.

• Brunton, G. 1927-1930. Qau and Badari, 3 vols. British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account [44, 45, 50] (29th year). London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt, Bernard Quaritch.

• Mackay, E., H. Lankester and F. Petrie 1929. Bahrein and Hemamieh. British School of Archaeology in Egypt and Egyptian Research Account [47]. London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt, Bernard Quaritch.

• Paribeni, R. 1940. “Scavi nella necropolis di El-Hammamiya.” Aegyptus 20: 277-293.

• Timm, S. (ed.) 1984-1992. Das Christliche-Koptische Ägypten in Arabischer Zeit: Eine Sammlung Christicher Stätten in Ägypten in Arabischer Zeit unter Ausschyss von Alexandria, Kairo, des Apa-Mena-Klosters (Der Abu Mina), der Sketis (Wadi n-Natrun) und der Sinai-Region. Vol. 3, 1078-9. Weisbaden: Dr Ludwig Reichert.

Json data

Json data