DAYR ABŪ MĪNĀ

| Arabic | دير أبو مينا |

| English | Abu Mena | Deir Abu Mina |

| French | Abou Mena | Abou Mina | Abu Mena | Abu Mina |

| DEChriM ID | 49 |

| Trismegistos GeoID | 2711 |

| Pleiades ID | 727105 | PAThs ID | 116 |

| Ancient name | - |

| Modern name | Dayr Abū Mīnā |

| Latitude | 30.841158 |

| Longitude | 29.662742 |

| Date from | 390 |

| Date to | 1100 |

| Typology | Pilgrimage centre |

| Dating criteria | - |

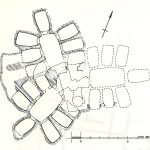

| Description | Dayr Abū Mīnā, perhaps better known simply as ‘Abū Mīnā’ (the ancient name of which is not known), is an extensive Late Antique pilgrimage site, the very earliest phases of which dates from the late fourth century (Grossmann 1998b: 282). Parts of the site were destroyed during the Persian occupation, with certain features repaired after their departure during a brief period of resurgence, which was then disrupted by the Arab invasion (Grossmann 1998b: 297-298; Kościuk 2003). Occupation extended up until the 12th century, at which point it was completely abandoned in response to the decline in pilgrimage-related activity (which was the reason for the townʼs existence in the first place) (Grossmann 1998b: 281; Kościuk 2003: 45). The site is situated c. 45km south-west of Alexandria, accessed via a pilgrimage route extending from the shore of lake Mareotis, which runs through the town and leads directly to the Great Basilica and associated ‘pilgrim court’ (Grossman et al. 1991: 465). The site includes at least five churches, in addition to features intended to accommodate pilgrims (i.e., baths, rest-houses etc.) as well as residential and industrial areas, the later, namely comprising wine and ceramic production (including the famous pilgrim flasks), was clearly intended for exportation given the production capacity which would have far exceeded the needs of the local community (Grossmann 1998b: 298-299). Around the middle of the 13th century, the supposed relics of the saint were found by Bedouins, and then transferred to the church of St. Menas in Cairo in the mid-14th century (Grossmann 1998: 298). The Small Basilica ii. Crypt Church 2 (Justinian Conch-Church) iii. Crypt Church 3 (Late Five-Aisled Basilica) Great Basilica ‘Southern Hemicyclium’ Eastern Church North Basilica Misc. Prior to the development of the pilgrim industry, the region originally functioned as a cemetery (at least the area to the south of the pilgrimage complex), hence the saint’s burial here, with small statuettes of monkeys and miniature stelae of the god Horus-Harpocrates discovered by Kaufmann indicating the earlier, non-Christian nature of the region (Kauffmann 1910: 71; Grossmann 1998b: 282, 293). Additionally, numerous earlier hypogea have been found, further proving that at least the central area was originally a necropolis (Grossmann et al. 1998: 43). Once the area became a renowned pilgrimage location, it seems that wealthy Alexandrian families continued to use the area as a burial ground, due to proximity to the saint, with numerous residential buildings including chapels which incorporated undergound burial chambers; one of these chapels even included a baptistery (Grossmann 1998b: 293; id 2002: 214-215, 333-334, fig. 26). |

| Archaeological research | Given the size, state of preservation and importance of the site for early Christian studies, Dayr Abū Mīnā has seen extensive archaeological investigation. The first work was directed by C.-M. Kaufmann in the early 20th century, between 1905 and 1907. This was followed by the rather sporadic fieldwork of several teams who conducted both excavations and surveys in the early to mid-20th century. The first among these was the Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria between 1925 and 1929, followed by F. W. Deichmann in 1934 (Deichmann 1937), J. B. Ward Perkins in 1942 (Ward-Perkins 1949), and the Coptic Museum in Cairo in 1951 and 1952 (Labib 1951-1952). Between 1961 and 1974, the site was excavated under the joint direction of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Kairo and the Franz Joseph Dölger Institut Bonn. This work was interrupted when the area was transformed into a military zone between 1969 and 1975. From 1975 onwards, archaeological work has been under the direction of P. Grossmann, again for the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Kairo (Litinas 2008: ix). In 2001, the site was added to the list of World Heritage in Danger list due to the rising water tables, a fact already noted during excavations (i.e., Grossman et al. 1998: 56). |

• Abd el-Aziz Negm, M. 1993. “Recent Discoveries at Abû Mînâ.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 32: 129-137.

• Abd el-Aziz Negm, M. 1998b. “An Ancient Village Discovered Near Abu-Mina (5th-6th cent. A.D.).” In L’Egitto in Italia dall’antichità al medioevo: atti del 3. Congresso internazional italo-egiziano, Roma, CNR-Pompei, 13-19 novembre 1995, edited by N. Bonacasa, M. C. Caro, E. C. Rortale and A. Tullio, 307–312. Rome: Consiglio nazionale delle ricerche.

• Abd’al-Aziz, M. and J. Kościuk. 1990. “The Private Roman Bath Found Nearby Abû Mînâ (Egypt).” In Akten des XIII. Internationalen Kongresses für Klassische Archäologie, Berlin 1988, 442-445. Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern.

• Brenk, B. 1995. “Der Kultort, seine Zugänglichkeit und seine Besucher.” In Akten des XII. Internationalen Kongresses für Christliche Archäologie, Bonn 22.–28. September 1991, Münster 1995, vol. I, edited by E. Dassmann and J. Engemann, 69–122. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

• Castelfranchi, M. F. 1995. “Battisteri e pellegrinaggi.” In Akten des XII. Internationalen Kongresses für Christliche Archäologie, Bonn 22.–28. September 1991, Münster 1995, vol. I, edited by E. Dassmann and J. Engemann, 234–248. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

• Deichmann, F. W. 1937. “Zu den Bauten der Menas-Stadt.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1937: 75-86.

• Engemann, J. 1987. “Elfenbeinfunde aus Abu Mena/Ägypten.” Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum 30: 172-186.

• Engemann, J. 1989. “Das Ende der Wallfahrten nach Abû Mînâ und die Datierung früher islamischer glasierter Keramik in Ägypten.” Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum 32: 161-117.

• Engemann, J. 1998. “Ein Tischfuß mit Dionysos-Satyr-Darstellung aus Abu Mina/Ägypten.” Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum 41: 169–177.

• Falls, J. C. E. 1913. Three Years in the Libyan Desert: Travels, Discoveries, and Excavations of the Menas Expedition (Kaufmann Expedition). London: T. F. Unwin.

• Grossmann, P. 1973. “Abu Mena. Grabungen von 1961 bis 1969.” Annales du service des antiquités d’Égypte 61: 37-48.

• Grossmann, P. 1977. “Abu Mena. Achter vorläufiger Bericht. Kampagnen 1975 und 1976.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 33: 35-45.

• Grossmann, P. 1981. “Recenti risultati dagli scavi di Abu Mina.” Corsi di Cultura e Arte Ravennate e Bizantina 28: 125.

• Grossmann, P. 1982. “Abu Mina. Zehnter vorläufiger Bericht. Kampagnen 1980 und 1981.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 38: 131-154.

• Grossmann, P. 1983a. “The „Gruftkirche“ of Abu Mina During the Fifth Century A.D.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 25: 67–71

• Grossmann, P. 1983b. “Abu Mina.”Göttinger Miszellen 69: 83-88.

• Grossmann, P. 1983c. Report on the Excavation in Abu Mina. (April-May 1981).” Annales du service des antiquités de l’Égypte 69: 81-86.

• Grossmann, P. 1984. “Neue Funde aus dem Gebiet von Abu Mina.” In Actes du Xe Congrès International d’Archéologie Chrétienne. Thessalonique Sept.-Oct. 1980, vol. 2, 141-151. Città del Vaticano: Pontificio istituto di archeologia Cristiana.

• Grossmann, P. 1986. Abû Mînâ. A Guide to the Ancient Pilgrimage Center. Cairo: Fotiadis & co. Press.

• Grossmann, P. 1989. Abû Mînâ I. Die Gruftkirche und die Gruft. Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern.

• Grossmann, P. 1991. “Abu Mina, 12. Vorläufiger Bericht.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1991: 457-486.

• Grossmann, P. 1995a. “Report on the Excavation at Abû Mīnâ in Spring 1994.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 34: 149-159.

• Grossmann, P. 1995b. “Abu Mena, 13. Vorläufiger Bericht.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1995: 389-423.

• Grossmann, P. 1995c. “Neue Funde aus Abu Mina.” In Akten des XII. Internationalen Kongresses für Christliche Archäologie. Bonn 22.–28. September 1991, vol. 2, edited by E. Dassmann and J. Engemann, 825-832. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

• Grossmann, P. 1998a. “Abû Mînâ.” In Ägypten in spätantik-christlicher Zeit. Einführung in die koptische Kultur, edited by M. Krause, 269–293. Wiesbaden: Heinrich Bacht.

• Grossmann, P. 1998b. “The Pilgrimage Center of Abû Mînâ.” In Pilgrimage and Holy Space in Late Antique Egypt, edited by D. Frankfurter, 281-302. Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill.

• Grossmann, P. 1999a. “Report on the Excavation at Abû Mīnâ in Spring 1997.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 38: 65-73.

• Grossmann, P. 1999b. “Report on the Excavation at Abû Mīnâ in Spring 1998.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 38: 75-84.

• Grossmann, P. 1999c. “Abû Mînâ. Eine der letzten Städtegründungen der Antike.” In Stadt und Umland. Neue Ergebnisse der archäologischen Bau- und Siedlungsforschung. Bauforschungskolloquium in Berlin vom 7. Bis 10. Mai 1997 veranstaltet com Architektur-Referat des DAI, edited by E.-L. Schwander and K. Rheidt, 287-293. Mainz: P. von Zabern.

• Grossmann, P. 2002. Christliche Architektur in Ägypten, 141, 210-216, 333-337, 401-412, 489-491. Leiden: Brill.

• Grossmann, P. 2004. Abu Mina II. Das Baptisterium. Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern.

• Grossmann, P., F. Arnold and J. Kościuk. 1997. “Report on the Excavation at Abu Mina in Spring 1995.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 36: 83-98.

• Grossmann, P., F. Arnold and J. Kościuk. 1998. “Report on the Excavation at Abû Mīnâ in Spring 1996.” In Actes du Symposium des fouilles Copte, Le Caire 7-9 Novembre 1996, 43-56. Cairo: Société d’archéologie copte.

• Grossmann, P. W. Hölze, H. Jaritz and J. Kościuk. 1991. “Abū Mīna. Zwölfter vorläufiger Bericht. Kampagnen 1984 – 1986.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1991, 457-486.

• Grossmann, P., W. Hölze, H. Jaritz and J. Kościuk. 1995. “Abū Mīna. Dreizehnter vorläufiger Bericht. Kampagnen 1987 – 1989.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1995, 389-423.

• Grossmann, P. and H. Jaritz. 1980. “Abu Mena. Neunter vorläufiger Bericht. Kampagnen 1977, 1978 und 1979.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 36: 204-227.

• Grossmann, P., H. Jaritz and C. Römer. 1982. “Abū Mīna. Zehnter vorläufiger Bericht. Kampagnen 1980 und 1981.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 38: 131-154.

• Grossmann, P. and J. Kościuk. 1991. “Report on the Excavation at Abū Mīna in Autumn 1989.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 30: 65-75.

• Grossmann, P. and J. Kościuk. 1992. “Report on the Excavations at Abū Mīna in Autumn 1990.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 31: 31-41.

• Grossmann, P. and J. Kościuk. 1993. “Report on the Excavation at Abū Mīna in Autumn 1991.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 32: 73-84.

• Grossmann, P. and J. Kościuk. 2001. “Report on the Excavation at Abū Mīna in Spring 2000.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 40: 97-108.

• Grossmann, P., J. Kościuk and M. Abdal Aziz. 1994. “Report on the Excavation at Abū Mīna in Spring 1993.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 33: 91-104.

• Grossmann, P., J. Kościuk and H.-G. Severin. 1984. “Abū Mīna. Elfter vorläufiger Bericht. Kampagnen 1982 und 1983.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 40: 123-151.

• Grossmann, P., M. Meinecke and H. Jaritz. 1970. “Abu Mena. Siebenter vorläufiger Bericht.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 26: 55-82.

• Grossmann, P. and I. Stollmayer. 2000. “Report on the Excavation at Abū Mīnā in Spring 1999.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 39: 103-117.

• Hans-Christoph, N. 1991. “Der spätrömische Münzschatz aus der Gruftkirche von Abu Mina.” In Tesserae. Festschrift für Josef Engemann, edited by E. Dassmann and K. Thraede, 278–290. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

• Kaufmann, C. M. 1908b. La découverte des sanctuaires de Ménas dans le désert de Maréotis. Rapports sur les fouilles exécutées par C. M. Kaufmann et I. C. E. Falls dans le sanctuaire national des anciens chrétiens d’Égypte. Alexandria: Société de publications Égyptiennes.

• Kaufmann, C. M. 1909. Der Menastempel und die Heiligtümer vom Karm Abu Mena in der Mareotiswüste. Ein Führer durch die Ausgrabungen der Frankfurter Expedition. Frankfurt: Joseph Baer & co.

• Kaufmann, C. M. 1910. Die Menasstadt und das Nationalheiligtum der altchristlichen Aegypter in der westalexandrinischen Wüste. Ausgrabungen der Frankfurter Expedition am Karm Abu Mina 1905–1907, vol. 1. Leipzig: K. W. Hiersemann.

• Kaufmann, C. M. 1924. Die Heilige Stadt der Wüste. Unsere Entdeckungen, Grabungen und Funde in der altchristlichen Menasstadt weiteren Kreisen in Wort und Bild geschildert. Kempten: J. Kösel & F. Pustet.

• Kościuk, J. 1992a. “Some Early Medieval Houses in Abu Mina (Egypt).” In Actes du IVe Congres International d’Études Coptes – Louvain-la-Neuve 1988, Vol. I: Art et Archéologie, edited by M. Rassart-Debergh and J. Ries, 158-167. Louvain: Peeters.

• Kościuk, J. 1992b. “A Conical Sundial from Abū Mīnā.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 31: 43-54.

• Kościuk, J. 1992c. “Typological Observations on Early Medieval Houses in Abu Mina.” In Sesto Congresso Internazionale di Egittologia. Atti, Turin 1992 vol. I, edited by J. Leclant, 375-382. Turin: International Association of Egyptologists.

• Kościuk, J. 1995. “The Last Phase of the Abū Mīnā Settlement.” In Akten des XII Internationalen Kongresses für Christliche Archäologie, Bonn 22-28 September 1991, vol. 2, edited by E. Dassmann and J. Engemann, 941-949. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

• Kościuk, J. 1998. “The Market Place of the Mediaeval Settlement in Abu Mina.” In Themelia. Spätantike und koptologische Studien, edited by M. Krause and S. Schaten, 187-212. Wiesbaden: Dr Ludwig Reichert.

• Kościuk, J. 2003. “The Latest Phase of Abu Mina – The Mediaeval Settlement.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie Copte 42: 43-54.

• Krause, M. 1978. “Karm Abu Mena.” In Reallexikon zur byzantinischen Kunst, vol. 3, cols. 1116-1158. Stuttgart: A. Hiersemann.

• Labib, P. 1951-1952. “Fouilles de musée Copte à Saint-Ménas.” Bulletin d l’Institut d’Égypte 34: 133-138.

• Litinas, N. ed. 2008. Greek Ostraca from Abu Mina (O.AbuMina). Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter.

• Meinardus, O. F. A. 1965. Christian Egypt. Ancient and Modern, 141–145. Cairo: Cahiers d’histoire égyptienne.

• Müller-Wiener, W. 1965. “Abu Mena. 3. Vorläufiger Bericht.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 20: 126-137.

• Müller-Wiener, W., J. Engemann and F. Traut. 1966. “Abu Mena. 4. Vorläufiger Bericht.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 21: 171-187.

• Müller-Wiener, W., J. Engemann and F. Traut. 1967. “Abu Mena. 5. Vorläufiger Bericht.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 22: 206-224.

• Müller-Wiener, W. 1967. “Abu Mena. 6. Vorläufiger Bericht.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1967: 457-480.

• Prinz, F. 1995. “Hagiographische Texte über Kult- und Wallfahrtsorte.” In Akten des XII. Internationalen Kongresses für Christliche Archäologie, Bonn 22.–28. September 1991, Münster 1995, vol. I, edited by E. Dassmann and J. Engemann, 310-328. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

• Reekmans, L. 1980. “Siedlungsbildung bei spätantiken Wallfahrtsstäatten.” In Pietas, Festschrift für Bernhard Kötting, edited by E. Dassmann and K. S. Frank, 325-355. Münster: Aschendorff.

• Rodziewicz, R. 2003. “Philoxenite: Pilgrimage Harbour of Abu Mina.” Bulletin de la société d’archéologique à Alexandrie 47: 27–47.

• Schläger, H. 1963. “Abu Mena, erster vorläufiger Bericht.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 19: 114-120.

• Schläger, H. 1964. “Die neueren Grabungen in Abu Mena.” In Christentum am Nil. Internationale Arbeitstagung zur Ausstellung “Koptische Kunst”, Essen, Villa Hügel, 23-25- Juli 1963, edited by K. Wessel, 158–174. Recklinghausen: Aurel Bongers.

• Schläger, H. 1965. “Abu Mena, zweiter vorläufiger Bericht.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 20: 122-125.

• Timm, S. (ed.) 1984-1992. Das Christliche-Koptische Ägypten in Arabischer Zeit: Eine Sammlung Christicher Stätten in Ägypten in Arabischer Zeit unter Ausschyss von Alexandria, Kairo, des Apa-Mena-Klosters (Der Abu Mina), der Sketis (Wadi n-Natrun) und der Sinai-Region. Vol. 3, 1267. Weisbaden: Dr Ludwig Reichert.

• Ward Perkins, J. B. 1949. “The Shrine of St. Menas in the Maryût.” Papers of the British School in Rome 17: 26-71.

• Wortmann, D. 1971. “Griechische Ostraka aus Abu Mena.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 8: 41-69.

For bibliographies regarding the cult of St. Menas and the pilgrim industry at Dayr Abū Mīnā, see: Litinas, N. ed. 2008, p. 324-326.

Json data

Json data