KŪM AL-AḤMAR SAWĀRIS

| Egyptian | Ḥw.t-nsw |

| Arabic | الكوم الأحمر سوارس | شارونة |

| English | Kom al-Ahmar |

| DEChriM ID | 54 |

| Trismegistos GeoID | 2793 |

| Pleiades ID | 736925 | PAThs ID | 432 |

| Ancient name | - |

| Modern name | Kūm al-Aḥmar Sawāris |

| Latitude | 28.568732 |

| Longitude | 30.864670 |

| Date from | -2700 |

| Date to | 850 |

| Typology | City |

| Dating criteria | - |

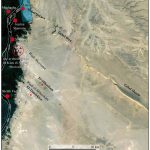

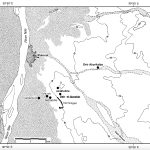

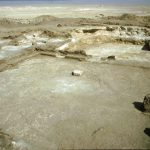

| Description | Šārūna/al-Kūm al-Aḥmar, denoted el-Kom el-Aḥmar/Sawāris in older publications, is located in Middle Egypt on the eastern bank of the Nile, 3km south of the village of Šārūna, hence the name. Qarāra is 8.6km to the north and al-Bahnasā (Oxyrhynchos) 21km to the west. It is situated on the border between the modern-day extension of the agricultural area and the desert. The site dates back to the Second/Third Dynasty and has traditionally been identified with the Pharaonic locality of Ḥw.t-nsw, which is documented since the Old Kingdom (Gonzálvez et al., 2009: 266). In the Middle Kingdom, it appears to have served as the capital of the 18th nome of Upper Egypt, while in the Ptolemaic era it was the capital of the 17th nome (Gonzálvez et al., 2009: 266). Written sources are basically non-existent after the Ptolemaic period, and the Coptic name of the site has not survived. The site comprises a main necropolis area with associated rock-cut tombs dating from the Sixth Dynasty, the first intermediate period and the Ptolemaic period, with the remains of a temple built by Ptolemies I and II, on top of which is a funerary basilica, as well as other areas of Christian (re-)occupation (Huber 2017: 1). It is understood that the whole settlement was abandoned in the seventh or eighth century (Huber 2007: 37) Settlement Area Main Necropolis Although several phases of occupation of U20 have so-far been identified, it is difficult to develop a secure chronology due to the excessive looting and subsequent destruction of much of the area. In the courtyard of the tomb are several funerary shafts, totaling to at least 20, one of which was reused during the Byzantine period when the underground section of the hypogeum was transformed into a kitchen (Gonzálvez et al. 2009: 265, 269; Isodoro et al. 2009: 244). Numerous shaft tombs were excavated during the Ptolemaic period, partially destroying the eastern end of the portico (Gonzálvez et al. 2009: 271). The second-best represented period of occupation was roughly between the fifth and sixth centuries CE, which perhaps included an industrial installation dedicated to textiles (Gonzálvez et al. 2009: 271). The latest phases show that the sudden collapse of a large part of the roof restricted the occupation, but still saw occasional use as a seasonal shelter for livestock (Gonzálvez et al. 2009: 272). Christian Occupation The original church appears to have been erected over a single chambered tomb constructed of burned brick, thought to have been the tomb of a saint, or perhaps a local hermit, which was subsequently transformed into a crypt with the construction of the church (Huber 2017: 5). This crypt was accessible from the church via the addition of a staircase, and was situated under the sanctuary. The floor of the church’s nave is densely packed with graves and is surrounded by a vast cemetery (extending more than 200m around the church), only some of which has been excavated, revealing some 1000 burials (Huber 2006: 58; Huber 2007: 37). All of these burials are simple pits, with the deceased extended supine, oriented on an east-west axis (with their heads to the west). A few datable artefacts, including coins, allow the construction of the first church to be situated in the last quarter of the fourth century, or the beginning of the fifth, with the second church constructed perhaps in the middle of the sixth century (Huber 2017: 5). A lamp found beneath the foundations of the church dates from the third century (Huber 2007: 37). The entire site appears to have originally served as a Ptolemaic cemetery comprised of simple pit burials, which acted as the counterpart of the necropolis of rock-cut tombs. Material from these earlier graves have included pottery, offering tables, animal bones, and a number of skeletons adorned with amulets depicting Egyptian deities and symbols (Huber 2017: 6). Dayr al-Qarābīn The tower is almost a perfect square, the walls of which are only three brick length wide and are made of unfired brick. There does not appear to have been external access to the tower on the ground floor, the building being instead accessed on the first floor via the help of a wooden draw-bridge which connected to a free-standing staircase (Huber 2012: 73). Within the tower is a vertical shaft which opens into a horizontal corridor leading east into an underground complex. This appears to have been a storage area, and includes a large water cistern. This complex appears to have been accessible from the outside via a small, and secret entrance, making it possible to enter the tower unobserved from the outside, which in turn provided access to these supplies (Huber 2012: 72, 76). al-Ġalīda There is a tower at the highest point of the hermitage. Like the one at Dayr al-Qarābīn, this tower is a square building of unbaked clay bricks (Huber 2012: 78). Similarly to that of Dayr al-Qarābīn, it shows the beginnings of an underground, unfurnished corridor. There is no access via the ground floor, and no indication of a free-standing staircase like at Dayr al-Qarābīn, indicating that access to the tower was gained via a pulley or a ladder. Based on the ceramic assemblages, the tower can be dated from the eighth to tenth centuries CE, with a high concentration of glazed pottery of the type “Fayyumi ware”, which is documented from the eight to ninth centuries, as well as a number of LRA7 amphorae (Huber 2012: 79). Radiocarbon analysis of one of the bodies in the ‘monk cemetery’ appears to be from the ninth to tenth centuries (890-1020 AD, 95.4% probability) (Huber 2012: 79). The hermitage of al-Ġalīda became the center of religious life after Dayr al-Qarābīn was abandoned. Dayr Abū Kalba |

| Archaeological research | The first recorded mention of the site was by John Gardner Wilkinson in 1835, then, three years later, by Nestor l’Hôte, who noted the presence of a razed Ptolemaic temple built under Ptolemies I and II, and described the tomb of Pepianj-Jui. Mary Brodrick and A. Anderson Morten published a work on the tomb described by l’Hôte in 1899. This was followed by a visit by Grenfell and Hunt in 1907, who conducted limited excavation of a number of New Kingdom and Ptolemaic tombs, and noted that the structure mentioned by l’Hôte had since disappeared. They eventually abandoned the site due to the lack of papyri finds. Polish Egyptologist Tadeus Smolenski was responsible for the first extensive work on the site in 1907, carrying out exhaustive copying of the hieroglyphic texts of the tomb of Pepianj-Jui, and uncovering 18 blocks from a Ptolemaic temple which included the names of Ptolemies I and II. This was followed by sporadic expeditions by a number of Europeans, including Hermann Ranke in 1913 and Jean Capart in 1927. There was a lapse in scientific interest in the site until 1976, when the Egyptian Antiquities were forced to intervene in response to excessive looting. They closed the tomb of Pepianj-Jui and conducted three excavation campaigns between 1976 and 1981, which lead to the discovery of numerous tombs from the Old Kingdom. The Institute of Egyptology from the University of Tübingen became involved with the site in 1984, with six seasons of work conducted between 1984 and 1989, under the direction of Dr. Farouk Gomaà and Wolfgang Schenkel. This work included planimetric and epigraphic documentation of the decorated tombs of the Old Kingdom, as well as additional excavation work in the Old Kingdom cemetery and other parts of the necropolis. In 1990, Béatrice Huber takes over directorship, concentrating on the remains of the areas of Pharaonic occupation, and excavating the Christian basilica and the monastery of Dayr al-Qarābīn. Between 1994 and 2000, under the direction of Huber, the team focused on kom 5, where some of the previously cited temples appear to have been located. In 2004, Dr. Farouk Gomaà suggested the collaboration of the Museu Egipci de Barcelona, which was initiated in 2005. The work of the Catalan team would be concentrated in the main necropolis, including an imposing tomb from the Old Kingdom, while the team directed by Huber would continue to focus on the Byzantine occupation, specifically at Dayr al-Qarābīn (Gonzálvez et al., 2009: 268). |

• Brodrich, M. and A. A. Morton. 1899. “The Tomb of Pepi Ankh (Khua), near Sharuna.” Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology 21: 26-33.

• Capart, J. and M. Werbrouck. 1927. “Impressions de voyage.” Chronique d'Égypte; Bulletin périodique de la Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, Bruxelles (Brussels) 3: 103-136.

• Gestermann, L., F. Gomaà, B. Heiligmann, P. Jürgens and W. Schenkel. 1992. “Al-Kōm al-Ahmar/Šārūna 1991” Göttinger Miszellen 127: 89-111.

• Gonzálvez, L. M. 2007. “Kom el-Ahmar/Sharuna. Primera campana de la Misión de la Universidad de Tübingen/Museu Egipci de Barcelona.” ArqueoClub 8: 18-21.

• Gonzálvez, L. M. 2008. “Kom el-Ahmar/Sharuna. Segunda campana de la Misión de la Universidad de Tübingen/Museu Egipci de Barcelona.” ArqueoClub 9: 20-23.

• Gonzálvez, L. M. 2009. “Kom el-Ahmar/Sharuna. Tercera campana de la Misión de la Universidad de Tübingen/Museu Egipci de Barcelona.” ArqueoClub 10: 21-23.

• Gonzálvez, L. M., C. Belmonte, M. Taulé, F. Gomaà, B. Huber and A. Gamarra. 2009. “Trabajos de la Universidad de Tübingen en Kom al-Ahmar/Sharuna. La participación del Museu Egipci de Barcelona en el año 2006.” Trabajos de Egiptología. Papers on Ancient Egypt 265-275.

• Grenfell, B. P. and A. S. Hunt. 1902-1903. “Graeco-Roman Branch. Excavations at Hîbeh, Cynopolis and Oxyrhynchos.” Archaeological Report (Egypt Exploration Fund), 1-9.

• Grossmann, P. 2002. Christliche Architektur in Ägypten. Brill: Leiden. 428-9.

• Huber, B. 1998. “Al-Kom Al-Ahmar/Šaruna: decouverte d’une ville de province.” Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 82: 575-582.

• Huber, B. 2004a. “Die Grabkirche von Kom al-Ahmar bei Šaruna (Mittelägypten). Archäologie und Baugeschichte.” In Coptic Studies on the Threshold of a new Millennium II, edited by M. Immerzeel and J. van der Vliet, 1081-1103. Louvain: Peeters.

• Huber, B. 2004b. “Die Klosteranlage bei el-Kom el-Ahmar/Saruna (Mittelägypten).” Bulletin de la Société d'archéologie copte 43: 45-64.

• Huber, B. 2006. “Al-Kom al-Aḥmar/Sharūna: Different Archaeological Contexts – Different Textiles?” In Textiles in Situ: Their Find Spot in Egypt and Neighbouring Countries in the First Millennium CE, edited by S. Screnk, 57-68. Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung.

• Huber, B 2007a. “The Textiles of an Early Christian Burial from el-Kom el-Ahmar/Sharuna (Middle Egypt).” In Methods of Dating Ancient Textiles of the 1st Millenium AD from Egypt and Neighbouring Countries. Proceedings of the 4th Meeting of the Study Group 'Textiles of the Nile Valley, edited by A. De Moor and C. Fluck, 36-69. Tielt: Lannoo.

• Huber, B. 2007b. “Bautätigkeit und Wirtschaft in Deir el-Qarabin, Klosteranlage bei el-Kom el-Ahmar/Šaruna.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie copte 46: 61-71.

• Huber, B. 2008. “3000 ans d’histoire à Kom el-Ahmar/Saruna.” ArqueoClub 9: 24-28.

• Huber, B. 2012. “Von Türmen und einsiedeleien im raum Sharuna.” Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie copte 51: 69-99.

• Huber, B. 2017. “Sharuna.” In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History (online), edited by R. S. Bagnall, K. Brodersen, C. B. Champion, A. Erskine and S. R. Huebner. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah30412

• Huber, B. 2018. “The Early Christian Cemeteries of Qarara and Sharuna, Middle Egypt.” In Death and Burial in the Near East from Roman to Islamic Times. Research in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt, edited by C. Eger and M. Mackensen, 207- 226. Wiesbaden: Reichart Verlag.

• L’Hôte, N. 1840. Lettres écrites d’Égypte en 1838 et 1839, contenant des observations sur divers monuments égyptiens nouvellement explorés et dessinés. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères.

• Isidro, A. 2009. “Sharuna 2006-2008. Estudio antropológico y paleopatológico. Resultados preliminares.” ArqueoClub 10: 24-26.

• Isidro, A., L. Manuel Gonzálvez, M. Taulé, L. Moret, E. González, I. Galtés, X. Jordana and A. Malgosa. 2009. “Estudio preliminar de los restors humanos hallados en la necropolis de Sharuna (Universidad de Tübingen/Museu Egipci de Barcelona, campañas 2006-2008.” MUNIBE (Antropologia-Arkeologia) 60: 243-252.

• Moulin, B. and B. Huber. 2009. “Kôm al-Ahmar/Šaruna (Vallée du Nil, Moyenne-Égypte). Les apports de la géoarchéologie à la compréhension du site.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 65: 271-305.

• Pawlik, A. F. 2005. “The Lithic Industry of the Pharaonic Site Kom el-Ahmar in Middle Egypt and its Relationship to the Flint Mines of the Wadi el-Sheick.” Der Anschnitt 19: 193-209.

• Ranke, H. 1926. Koptische Friedhöfe bei Karâra und der Amontempel Scheschonks I. bei el Hibe. Berlin, Leipzig: de Gruyter.

• Schenkel, W. and F. Gomaà. 2004. Scharuna I. 2 vols. Mainz am Rhein: Saverne.

• Smolenski, T. 1907. “Le tombeau d’un prince de la Vie dynastie à Charouna.” Annales du Service des antiquités de l'Égypte 8: 149-153.

• Smolenski, T. 1908. “Les vestiges d’un temple ptolémaique à Kom-el-Ahmar près de Charouna.” Annales du Service des antiquités de l'Égypte 9: 3-6.

• Smolenski, T. 1910. “Nouveaux vestiges du temple de Kom-el-Ahmar près de Charouna.” Annales du Service des antiquités de l'Égypte 10: 26-27.

• Wilkinson, J. 1843. Modern Egypt and Thebes. London: John Murray.

Json data

Json data