DAYR AL-ʿIẒĀM

| Arabic | دير العظام |

| English | Deir el-Azzam |

| French | Deir el-Azzam | Deir el Aizam |

| DEChriM ID | 58 |

| Trismegistos GeoID | 61704 |

| Pleiades ID | - | PAThs ID | - |

| Ancient name | - |

| Modern name | Dayr al-ʿIẓām |

| Latitude | 27.157154 |

| Longitude | 31.167687 |

| Date from | 400 |

| Date to | 1200 |

| Typology | Monastic settlement |

| Dating criteria | - |

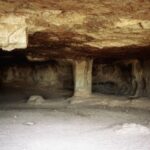

| Description | Dayr al-ʿIẓām is a monastic complex situated on top of the north-western part of the Ǧabal Asyūṭ al-Ġarbī, c. 3km south-west of the mausoleum of Šayḫ Abū Tūk. The complex comprised a church and a tower, as well as a number of buildings, some of which were two-storeys high at the beginning of the 20th century, bordered by an enclosure wall (Maspero 1900: 110; De Bock 1901: 88-90, fig. 100; Kahl 2014: 130). Outside of this enclosure wall, the complex was surrounded by a vast burial ground, understood as being the origin of the name, which translates to “The Monastery of Bones” (Maspero 1900: 115, Coquin and Martin 1991: 809). The church in the complex, which is today the only identifiable building on the ground, is understood to have been a three aisled basilica, with a khurus between the naos and sanctuary, a 7th century innovation which then gives a 7th century terminus post quem for the construction (Grossmann 1991: 810; id 2002: 208; Eichner 2020: 15). The relevance of the site lies in its contentious association with the hermitage of St. John of Lykopolis, a renowned monastic figure of the fourth century (Kahl 2014: 134). C. Zuckerman conjectured in the mid-90s that a collection of letters, now known as the “Archive of Apa Iohannes” (see referenced artefacts), which make reference to an anchorite named Apa John, originally derived from Dayr al-ʿIẓām or the surrounding mountainous area of Asyūṭ (Zuckerman 1995; Eichner 2020: 15). While these texts could be seen to support the association of this site with the hermitage of St. John of Lykopolis, the fact remains that the provenance of these texts is not certain, nor is it certain that, even if they do originate from Dayr al-ʿIẓām, the figure referenced in the letters is John of Lykopolis or another figure named John (following van Minnen 1994: 80-84, Zuckerman 1995: 188-194 and Fournet 2020: 13, we consider that the Apa John of the archive is one and the same as John of Lykopolis). However, given the fact that the texts are paleographically dated to the fourth century, and the toponyms mentioned are within the immediate surroundings of Asyūṭ, it is a plausible connection (Zuckerman 1995: 191). Nonetheless, this does not concretely associate the monastic complex of Dayr al-ʿIẓām with St. John’s actual hermitage (Wipszyka 2009: 83-85). These texts were presumed by Zuckerman to have been those uncovered during the 1897 excavation at Dayr al-ʿIẓām, led by Farag Ismail and Yassa Tadros. The associated publication references papyri found at the commencement of work, which Maspero states were transported to the Museum of Giza: “… des objects et des fragments de livres coptes recueillis au Déir el-Aizâm, qui sont conserves au Musée.” (Maspero 1900: 109). Considering the fact that there are no such items currently listed at the museum, Zuckerman put forward the idea that they were perhaps sold (to none other than Grenfell and Hunt) in order to help finance the excavation (Zuckerman 1995: 192). In addition to the papyri fragments mentioned, the dig also uncovered a jar with some 30 lines of Coptic writing, dated 1156, naming the site as the monastery of “Apa Iohannes of the Desert” (Maspero 1900: 109-110, 116-118; Crum 1902: 33-34 (no. 8104), pl. 1; Coquin and Martin 1991: 809; Kahl 2014: pl. 11). This has further strengthened the association between Dayr al-ʿIẓām and the hermitage of John of Lykopolis (Coquin and Martin 1991: 809; Zuckerman 1995). Given the degree of disturbance of the monastic complex, only very limited information could be obtained during the 2009 survey of the Asyut Project. Isolated sherds of LRA1 were found, indicating occupation from the fifth century onwards, though the material from the dump on the slope of the hill below the original monastic area also revealed Aswan ceramic dating from the 8th-10th centuries, glazed Islamic sherds dating beyond the 12th and 13th centuries, and a limited amount of material from disturbed graves dating from the 4th-7th centuries (Eichner and Beckh 2010: 207; id 2020: 34-36, 115). Though limited, the material finds from the surrounding area indicate that it was settled in late antiquity, rather than exclusively used as a necropolis (Eichner and Beckh 2010: 208). Perhaps a more likely location of the hermitage of St. John of Lycopolis is a complex of rock-cut tombs, some 200 meters away from the monastic complex. These tombs, belonging to local nomarchs of the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom, like many Pharaonic tombs, appear to have been inhabited by anchorites during the early Christian period (Kahl 2007a: 71-72; id 2014: 128). The inner hall of one of these tombs, tomb IV (Asyut Project no. N12.2), shows faint remnants of a figural painting above which an iota and omega are visible, understood to be remnants of the name Ιωάννης – ‘John’ (Eichner & Beckh 2010: 210; Kahl 2014: 132 pl. 9; Eichner 2020: 16 pl. 2a and 2b). Additionally, architectural modifications of the space seem to have been enacted in order to transform it into a place of worship, leading to the subsequent assumption that a saint named John was venerated here (El-Khadragy 2006: 89-90). As with the abovementioned letters, whether or not the figure depicted in the tomb complex is John of Lykopolis, however, or another local figure named John, remains cause for contention. The fact that this tomb, and tombs II and III, (Asyut Project nos. O13.1 and N12.1) form a joint complex that seems to coincide with the architectural descriptions of the hermitage of St. John, which comprised of three rooms, then leads to the understanding that the figure venerated here was indeed John of Lykopolis (Kahl 2007a: 139; id 2007b: 82-83; id 2014: 135; Eichner and Beckh 2020: 5-6). The disturbed context of these tombs as a result of looting as well as the presence of early excavators in the 19th and 20th centuries complicates attempts at interpreting much of the material. Nonetheless, a number of artefacts datable to the fourth century imply that the complex was indeed occupied in the 4th century, which further supports the association of this space with the hermitage of John of Lykopolis (Kahl 2014: 136). Regarding the countless funerary contexts, it is said that the church contained numerous graves, while the burials surrounding the monastic complex included single and multiple interments, buried in either wooden boxes or mats made of woven palm leaves (Maspero 1900: 100, 113). Interestingly, there were supposedly numerous occurrences of individuals wrapped in funerary shrouds decorated with crosses, as well as shrouds embroidered with Islamic formulas in Arabic (Maspero 1900: 113-114). |

| Archaeological research | The oldest (modern) description of the monastery associated with St. John’s hermitage is in al-Maqrīzī, although it is unclear as to whether this reference can be seen with relation to Dayr al-ʿIẓām. Steffan Timm, nonetheless, asserts such a connection (Wüstenfeld 1845: 102 nr. 45; Timm 1984-1992: 831). Given that Develliers and Jollois, two members of Napoleon’s expedition, explored the Ǧabal in 1799, it is possible that a description of the monastery could have been included in the Description de l’Égypte, but under a different name (Coquin and Martin 1991: 809; Eichner 2020: 11). The connection between these locations and what is known today as Dayr al-ʿIẓām was established by the Jesuit priest Michel Jullien in 1901, although Jullien did not make any connection between the monastic complex and the hermitage of John of Lykopolis (Jullien 1901: 208). The mountainous area of Asyūṭ, though not necessarily Dayr al-ʿIẓām, was visited by numerous Western antiquarians and archaeologists in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, majority of whom focused exclusively on the Pharaonic funerary material. The fact that many of these tombs were re-occupied in the Christian period by anchorites was of little interest or concern for these figures (Ryan 1995: 6). The first foreign excavation in the ancient cemetery of Asyūṭ was that of Émile Chassinat and Charles Palanque in 1903, followed by Ernesto Schiaparelli from 1905 to 1913 and D. G. Hogarth in 1906/1907. Although it is it not certain that any of these individuals specifically conducted work at Dayr al-ʿIẓām (though it is likely that at least some of them did, specifically Hogarth), it is important to mention their work here as they utilised tombs III and IV as a basis of operations during their excavation campaigns. As a result, the archaeological context of these areas is even more disturbed than is often the case, with not only the rubbish and refuse of these teams but also masses of material from other areas being present, as the latter was brought into these tombs to be inventoried, with much of it being discarded and left there (or used as kindling for fires) (Ryan 1995: 6; Kahl 2007a: 30-33; id 2014: 135). The first excavation specifically focusing on Dayr al-ʿIẓām seems to have been that of Yassa Tadros and Farag Ismail, two local Egyptians, who requested permission to conduct a self-financed excavation of the monastery in 1897. The brief publication that resulted from this was authored by Mohammed Effendi Chaban, the inspector who oversaw excavation, with an introduction and plan by Maspero (Maspero 1900). V. De Bock made a plan the following year, bringing to light a number of structures not seen, or not recorded, by Maspero, including the eastern part of the church. The plans of both men are notably imprecise. De Bock additionally made mention of the graves surrounding the complex, referencing the inclusion of children, which has led to the understanding that the surrounding cemetery area could not have served the monastery itself (Walters 1974: 233; Eichner 2020: 13-14). In April 1901, the complex was visited by S. Clarke, who too made reference to the heavily looted graves in the funerary area outside the complex, as well as a number of graves within the confines of the monastery (Clarke 1912: 178-179). As mentioned above, Hogarth likely also explored the monastery, and there are perhaps objects from the site currently in the collection of the British Museum, though details are limited (Ryan 1988, report 4; id 1995: 9; Eichner 2020: 13). The monastery is also mentioned by O. Meinardus and J. Doresse, with the later believing that it had indeed developed out of the hermitage of John of Lykopolis (Doresse 1971: 418). The monastic complex of Dayr al-ʿIẓām is almost completely destroyed today. This is due to rain, which has caused a great deal of erosion, but predominantly as a result of the Egyptian military, who, in the 1960s, destroyed much of the complex with dynamite (Grossmann 1991: 809; Eichner 2020: 13-14, fig. 4 and 5). Consequently, the structures mapped by Maspero and De Bock in the early 20th century, apart from the church, are no longer identifiable, while that which is identifiable was not included in these earlier plans (Eichner 2020: 17). The current condition of the complex has thus limited modern scholars in their capacity to conduct further studies. The most recent work in the area has been that of a joint German-Egyptian mission, titled the ‘Asyut Project’. The mission, which is a collaboration between the Freie Universität Berlin, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz and Suhag University, has been operating on the Ǧabal Asyūṭ since 2003. |

• de Bock, V. 1901. Matériaux pour servir à I'archéologie de I'Egypte chrétienne, 84, 88-90. Saint Petersberg: Eugéne Thiele.

• Clarke, S. 1912. Christian Antiquities in the Nile Valley: A Contribution Toward the Study of the Ancient Churches. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

• Coquin, R.-G. and M. Martin. 1991. “Dayr aI-Izam.” In The Coptic Encyclopedia. vol. 3, edited by A. S. Atiya, 809. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

• Crum, W. E. 1902. Coptic Monuments. Cairo: Institut français d?archéologie orientale.

• Doresse, J. 1971. “Les anciens monastères coptes de Moyenne-Égypte (du Gebel-et-Teir à Kôm-Ishgaou) d’après l’archéologie et l’hagiographie.” PhD Dissertation, University of Paris.

• Eichner, I., with contribution by T. Beckh. 2020. Der Survey der spätantiken und mittelalterlichen christlichen Denkmäler in der Nekropole von Assiut/Lykopolis (Mittel Ägypten). Weisbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

• Eichner, I. and T. Beckh. 2010. The Late Antique and Medieval Monuments of the Gebel Asyut al-Gharbi.” Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 39: 207-210.

• El-Khadragy, M. 2006. “New Discoveries in the Tomb of Khety II at Asyut.” The Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology 17: 79-95.

• Fournet, J.-L. 2020. The Rise of Coptic: Egyptian versus Greek in Late Antiquity. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press: 13.

• Grossmann, P. 1982. Mittelalterliche Langhauskuppelkirchen und verwandre Typen in Oberägypten. Eine studie zum mittelalterlichen Kirchenbau in Ägypten. Glückstadt: J. J. Austin.

• Grossmann, P. 1991. “Dayr al-Izam. Architecture.” In The Coptic Encyclopedia. vol. 3, edited by A. S. Atiya, 809-810. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

• Grossmann, P. 2002. Christliche Architektur in Ägypten, 208-210. Leiden: Brill.

• Jollois, J. B. P. and R. E. du Terrage Devilliers. 1821-1829. Description de l’Égypte, vols. 4 and 15. Paris: C. L. F. Panckoucke.

• Jullien, M. 1901. “A travers les ruines de la Haute Egypte.” Études 88: 204-217.

• Kahle, P. 1954. Balaizah 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press.

• Kahl, J. 2007a. Ancient Asyut: The First Synthesis After 300 Years of Research. Weisbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag.

• Kahl, J. 2007b. “Corridor Connecting Tomb III and IV.” Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 36: 82-83.

• Kahl, J. 2014. “Gebel Asyut al-Gharbi in the First Millennium AD.” In Egypt in the First Millennium AD. Perspectives From New Fieldwork, edited by E. O’Connell, 127-138. Leuven, Paris, Walpole: Peeters.

• Kahl, J. 2015. “The Cave of John of Lykopolis.” In Christianity and Monasticism in Middle Egypt: Al-Minya and Asyut, edited by G. Gabra and N. Takla, 255-263. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

• Kahl, J., A. Alansary, U. Verhoeven, T. Beck, E. Czyzewska-Zalewska and A. Killian. 2017. “The Asyut Project: Twelfth Season of Fieldwork (2016).” Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 46: 113-151.

• Kahl, J., M. el-Khadragy and U. Verhoeven. 2005. “The Asyut Project: Fieldwork Season 2004.” Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 33: 159-167.

• Kahl, J., M. el-Khadragy and U. Verhoeven. 2006. “The Asyut Project: Third Season of Fieldwork.” Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 34: 241-249.

• Kahl, J., M. el-Khadragy and U. Verhoeven. 2007. “The Asyut Project: Fourth Season of Fieldwork (2006).” Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 36: 81-103.

• Kahl, J., M. el-Khadragy and U. Verhoeven, with a contribution by Abd el-Naser Yasin. 2008. “The Asyut Proejct: Fifth Season of Fieldwork (2007).” Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 37: 199-218.

• Kahl, J., M. el-Khadragy, U. Verhoeven, S. Prell, I. Eichner and Th. Beckh. 2010. “The Asyut Project: Seventh Season of Fieldwork (2009).” Studien zur altägyptischen Kultur 39: 191-210.

• Lantschoot, A. van. 1929. Recueil des colophons des manuscrits chrétiens d’Egypte 2 vols. Leuven: J.-B. Istas.

• Maspero, G. 1900. “Les fouilles de Deir el Aizam (septembre 1897).” Annales du Service des antiquités de l’Égypte 1: 109-119 and fig. 1.

• Meinardus, O. 1965. Christian Egypt, Ancient and Modern. Cairo: Cahiers d’histoire égyptienne.

• Timm, S. ed. 1984-1992. Das Christliche-Koptische Ägypten in Arabischer Zeit: Eine Sammlung Christicher Stätten in Ägypten in Arabischer Zeit unter Ausschyss von Alexandria, Kairo, des Apa-Mena-Klosters (Dēr Abū Mīna), der Skētis (Wādi n-Naṭrūn) und der Sinai-Region, vol 2, 829-831. Weisbaden: Dr Ludwig Reichert.

• Tudor, B. 2011. Christian Funerary Stelae of the Byzantine and Arab Periods from Egypt. Marburg: Tectum Verlag.

• Ryan, D. P. 1988. “The Archaeological Excavations of David George Hogarth at Asyut, Egypt 1906/1907.” PhD Dissertation, The Union Institute, Cincinnati.

• Ryan, D. P. 1995. “David George Hogarth at Asyut, Egypt, 1906-1907. The History of a “Lost”Excavation.” Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 5, 2: 3-16.

• Van Minnen, P. 1994. “The Roots of Egyptian Christianity.“ Archiv für Papyrusforschung und verwandte Gebiete 40: 71-85.

• Walters, C. C. 1974. Monastic Archaeology in Egypt. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

• Wipszycka, E. 2009. Moines et communauts monastiques en Égypte (IVe-VIIe siècles). Warsaw: Journal of Juristic Papyrology.

• Wüstenfeld, F. 1845. Macrizi’s Geschichte der Copten. Aus den Handschriften zu Gotha und Wien mit Übtersetzung und Anmerkungen. Göttingen: Dieterich.

• Zuckerman, C. 1995. “The Hapless Recruit Psois and the Mighty Anchorite, Apa John.” Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrology 32, 2: 183-194.

Json data

Json data