DŪŠ (KYSIS)

| Egyptian | Kš / Gš |

| Greek | Κυσις |

| Arabic | دوش | قصر دوش | قلعة دوش |

| English | Dush | Dosh |

| French | Douch |

| DEChriM ID | 1 |

| Trismegistos GeoID | 2761 |

| Pleiades ID | 776191 | PAThs ID | - |

| Ancient name | Kysis |

| Modern name | Dūš |

| Latitude | 24.580809 |

| Longitude | 30.716849 |

| Date from | -600 |

| Date to | 450 |

| Typology | Village |

| Dating criteria | Radiocarbon, numismatics, ceramic |

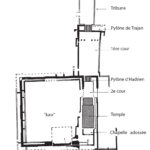

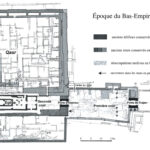

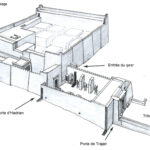

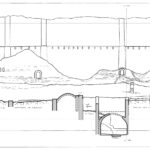

| Description | The site of Dūš, known as Kysis in antiquity, is a large town located in the south of Kharga Oasis, 17.5 km from Šams al-Dīn. As the first site in the Western Desert to be systematically excavated, the archaeological research conducted here has been on-going and extensive. The current chronology of the site consists of four main phases of occupation: phase 0 (Ptolemaic period, but also including the beginning of the fourth century BCE, based on a demotic ostracon, but also, among others, the temenos of the brick temple, radiocarbon dated to 787-429 BCE); phase I (1st-2nd centuries); phase II (transition period, end of 2nd/beginning of 3rd – end of 3rd/beginning of 4th centuries); phase III (Lower Empire, end of 3rd/beginning of 4th – beginning of 5th centuries), finally ending with the abandonment of the site in the mid-fifth century CE (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 209; Reddé, Dunand, Lichtenberg, Heim, Ballet 1990: 287). Notable features include a structure denoted ‘the Fort’, a temple complex, and a residential area (‘the village’). The 'Fort' (Kasr) All of the visible compartments inside the fort, however, are from a very late phase of occupation, understood to be contemporaneous with the use of the space by the Roman army (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 93, 170, 174). This military presence is attested to by the large number of military ostraca found both in the ‘Fort’, as well as the second courtyard of the temple (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 175). There is no papyrological evidence of the Roman military being present in Dūš prior to the fourth century CE, the period when the greatest expansion appears to have taken place (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 200; Gehad, Wuttmann, Whitehouse, Foad, Marchand 2013: 170). It was in fact, the departure of these soldiers which marks the abandonment of the site (Ghica 2012: 213). Considering the domineering appearance of the structure and the documented presence of the military, one understands the classification of the structure as a fort; however, the absence of towers, a solidly defended door, as well as the rarity of square forts, more likely point towards the use of the structure as perhaps a guard post, a granary, a group of magazines or a combination of all or some of these, as was probably the case with the old kasr, built some seven to eight centuries before its use by the Roman military (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 175). Religious Complex Trying to establish a comprehensive chronology of the complex is a difficult task considering the many and diverse architectural modifications carried out over an extensive period of time. There are, none the less, a number of significant chronological markers. The first pylon, restored in the early 1990s by M. Wuttmann, is attributed to Trajan, but it is clear that this was only the last in a series of modifications, while the construction of the monumental door that follows is dated to Hadrian (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 94). The foundation of this latter feature cuts an even earlier foundation, and the current temple is situated on top of remains of an earlier mud-brick structure, clearly indicating that the current structures are the result of a series of alterations (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 168; Gehad, Wuttmann, Whitehouse, Foad, Marchand 2013: 159). It appears that from the fourth century CE onwards, a number of areas of the temple were modified and compartmentalised in order to be re-used in contexts different from their original purpose, including their reoccupation by the military (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 93). It has also been theorised that the temple was transformed into an early Christian church (Sauneron et al. 1978: 31-33; Reddé 1999a: 80; Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 75, 94). This hypothesis is substantiated by the presence of Christian graffiti and dipinti, indicating the decommissioning of the temple (Wagner 1987: 57-58, 358; Ghica 2012: 214). A number of Greek ostraca found in the first and second levels of occupation, both dating from the end of the fourth century, ‘testify to the rapidity of the floors and support the hypothesis of a continuous redevelopment of the premises’ (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 98). The Village Building I Building IV The Painted House Christian Presence The Christian population at Dūš is discreet, but the evidence is undeniable. The most distinctive markers are onomastic; for example, among the soldiers stationed here for several decades, 361 of the 1843 had supposedly ‘Christian’ names (Reddé, Dunand, Lichtenberg, Heim, Ballet 1990: 287; Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire and Bonnet 2004: 206; Ghica 2012: 215). An additional key feature regarding the Christian presence at Dūš concerns a papyrological record of necrotaphs dated to the end of the third century CE (Reddé, Ballet, Lemaire, Bonnet 2004: 206). While informative, these papyri have led to the potentially skewed interpretation of the Christianness of those working in the necropolis. Consequently, the necropolis has become a key area of focus. Necropolises |

| Archaeological research | While having been visited by some European travellers in the 17th century, namely missionaries, the first description of the site was not provided until 1821 by Cailliaud. Herein he gives a brief description of the village and the temple, including copies of a number of inscriptions from the vault. This work was then followed by that of Hyde (published by Salt in 1819), Hoskins (1835), and Wilkinson (1843). Unlike Cailliaud, Hoskins offers a precise and accurate depiction of the temple, while also recognising the dedications to Trajan, Domitian and Hadrian. While Wilkinson identifies the dedication of the temple to Serapis and makes the correlation between Dūš and the ancient city of Kysis. Keeping with the times, the site was visited by those in search of papyrus, at which point the “Dossier of the Necrotaphs” was uncovered and published in 1897 by Grenfell and Hunt. The turn of the century made way for more scientific investigations to be carried out, with John Ball conducting the first survey in 1898. This was followed by the instigation of hydrological studies initially carried out by Beadnell, who was the first to describe the qanāt. A. Azadian (1927 & 1930) continued with these hydrological studies, and R. Naumann (1939) published a dimensional plan and section of both of the temples. The two world wars somewhat immobilised scientific investigations, but work was initiated again in the 50s by French scholar Serge Sauneron who published a number of works in 1954 and 1955. Sauneron, who went on to become the director of l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale (IFAO), then led the first proper excavation campaign on the site in 1976. A second campaign was planned for the same year but was prevented by Sauneron’s death. A second campaign was carried out in 1978-9 directed by Jean Gascou where the surroundings of the sanctuary were cleared and the first exploration of the necropolis was undertaken. Gascou maintained directorship for five seasons, throughout which time were the beginnings of the study of the ‘Fort’, surveying of the site (and the oasis in general), and the systematic epigraphic studies of the walls of the temple. In 1982, Guy Wagner was appointed director and fieldwork was put on a two-year pause while a number of scientific studies were conducted. In 1985, the management of the site was handed over to Michel Reddé who directed five campaigns (Reddé 2004: 9). From 1992, conservation and restoration work began to be conducted under the supervision of Michel Wuttmann, while the focus of excavators shifted to the site of ʿAyn Manāwir, 3.5 km to the west. Although limited, excavations were then again carried out at Dūš between 2008 and 2009 by Basem Gehad, under Michel Wuttmann's direction. Following a fortuitous discovery, the dig was restricted to a mud-brick house on the western side of the dromos, which features a number of wall paintings (Gehad, Wuttmann, Whitehouse, Foad, Marchand 2013: 158). After eight years of interruption, IFAO's mission at Douch was relaunched by Victor Ghica in 2022, with a first season dedicated to the reconstruction of a collapsed wall in the western part of the first court, next to Trajan's gate, and the anastylosis of the columns in the portico behind Trajan's gate (Ghica 2023). |

• Azadian, A. 1927. “Les sources de l'oasis de Khargeh.” Bulletin de l'Institut du désert d'Égypte 9: 83-88.

• Azadian, A. 1930. Les eaux d'Égypte I-III. Cairo: National Printing Office.

• Ballet, P. 1990. “La céramique du site urbain de Douch/Kysis.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 90: 298-301.

• Ballet, P. 2004. “Jalons pour une histoire de la céramique romaine au sud de Kharga. Douch 1985-1990.” In Douch III. Kysis. Fouilles de l’IFAO à Douch. Oasis de Kharga (1985-1990), edited by M. Reddé, 209-40. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Ballet, P. 2007. “Les amphores de Kysis/Douch (1985-1990). Oasis de Kharga.” In Amphores d’Égypte de la basse époque à l’époque arabe, edited by S. Marchand and A. Marangou. Cahiers de la céramique égyptienne 8: 481-7. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Barakat, H. N. and N. Baum. 1992. La végétation antique de Douch (Oasis de Kharga). Une approche macrobotanique. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Barbet, A. 2004. “Les peintures murals du bâtiment I.” In Douch III. Kysis. Fouilles de l’IFAO à Douch, oasis de Kharga (1985-1990), edited by M. Reddé, 87-91. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Bonnet, C. 2004. “L’église du village de Douch,” In Douch III. Kysis. Fouilles de l’IFAO à Douch, oasis de Kharga (1985-1990), edited by M. Reddé, 75-86. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Bousquet, B. 1996. Tell-Douch et sa région: géographie d’une limite de milieu à une frontière d’empire. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Bousquet, B. and M. Robin. 1999. “Les oasis de Kysis. Essai de definition géo-archéologique.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 99: 21-40.

• Cailliaud, F. 1821. Voyage à l’oasis de Thèbes et dans les déserts situés à l’Orient et à l’Occident de la Thébaïde fait pendant les années 1815, 1816 et 1817. Paris: Imprimerie royale.

• Carrié, J.-M. 2004. “Portarenses (douaniers), soldats et annones dans les archives de Douch, Oasis Major.” In Mélanges d’Antiquité tardive: Studiola in Honorem Noël Duval, edited by C. Balmelle, P. Chevalier and G. Ripoll, 261-74. Turnhout: Brepols.

• Castel, G. and F. Dunand. 1981. “Deux lits funéraires d’époque romaine de la nécropole de Douch.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 81: 79-110.

• Cuvigny, H. and G. Wagner. 1986. Les ostraca grecs de Douch (O. Douch) I. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Cuvigny, H. and G. Wagner. 1988. Les ostraca grecs de Douch (O. Douch) II. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Cuvigny, H. and G. Wagner. 1992. Les ostraca grecs de Douch (O. Douch) III. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Derda, T. 1991. “Necropolis Workers in Graeco-Roman Egypt in the Light of the Greek Papyri.” Journal of Juristic Papyrology 21: 13-36.

• Dils, P. 2000. “Der Tempel von Dush. Publikation und Untersuchungen eines ägyptischen Provinz Tempels der römischen Zeit.” PhD Dissertation, Cologne.

• Dunand, F. 1982. “Les “têtes dorées” de la nécropole de Douch.” Bulletin de la Société française d’égyptologie 93: 26-46.

• Dunand, F. 1985. “Les nécrotaphs de Kysis.” Cahiers de Recherches de l'Institut de papyrologie et d'égyptologie de Lille 7: 117-27.

• Dunand, F., J.-L. Heim, N. Henein and R. Lichtenberg. 1992. Douch I. La nécropole: exploration archéologique. Monographie des tombes 1 à 72: structures sociales, économiques, religieuses de l’Égypte romaine. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Dunand, F., J. L. Heim, N. Henein and R. Lichtenberg. 2005. La nécropole de Douch: exploration archéologique. II, Monographie des tombes 73 à 92: structures sociales, économiques, religieuses de l’Égypte romaine. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Dunand F., Heim J.-L., Lichtenberg R. 1998. “La vie dans l’extrême: Douch, Ier s. è. chr. - IVe s. è. chr.” In Life on the Fringe. Living in the Southern Egyptian Deserts during the Roman and Early-Byzantine Periods. Proceedings of a Colloquium Held on the Occasion of the 25th Anniversary of the Netherlands Institute for Archaeology and Arabic Studies in Cairo 9-12 December 1996, edited by O. E. Kaper, 95-138. Leiden: Research School CNWS.

• Dunand, F. and R. Lichtenberg. 1985. “Une tunique brodée de la nécropole de Douch.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 85: 133-148.

• Gascou, J. and G. Wagner. 1979. “Deux voyages archéologiques dans l’Oasis de Khargeh.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 79: 2-5.

• Gascou, J., P. Deleuze, Ch. Décobert, P. Vernus, G. Castel, D. Valbelle, M.-A. Bonhême, D. Vaillancourt, G. Andreu, G. Wagner, M. Rodziewicz and B. Menu. 1980. “Douch: rapport préliminaire des campagnes de fouilles de l’hiver 1978-1979 et de l’automne 1979.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 80: 287-345.

• Gautier, G. 1981. “Monnaies trouvées à Douch (Campagne de fouilles de 1976).” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 81: 111-114.

• Gehad, B., M. Wuttmann, H. Whitehouse, M. Foad and S. Marchand. 2013. “Wall Paintings in a Roman Style House at Ancient Kysis, Kharga Oasis.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 113: 157-182.

• Ghica, V. 2012. “Pour une histoire du christianisme dans le désert Occidental d’Égypte.” Journal des savants 2: 189-280.

• Ghica, V. 2016. “Vecteurs de la christianisation de l’Egypte au IVe siècle à la lumière des sources archéologiques.” In Acta XVI Congressus Internationalis Archaeologiae Christianae, Rome 22-28.9.2013, edited by O. Brandt and G. Castiglia, 199, 202, 241-249, fig. 3 and fig. h. Città del Vaticano: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana.

• Ghica, V. 2023. “Archéologie de la religion dans l’oasis de Kharga aux époques romaine et byzantine – Douch (2022).” Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l’étranger [on line], uploaded 1 June 2023, consulted 10 August 2024. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/baefe/9181; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/baefe.9181.

• Grenfell, B. P. and A. S. Hunt. 1897. New Classical Fragments and Other Greek and Latin Papyri. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

• Grimal, N. 1994. “Travaux de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale en 1993-1994.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 94: 383-480.

• Grimal, N. 1995. “Travaux de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale en 1994-1995.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 95: 539-645.

• Grimal, N. 1996. “Travaux de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale en 1995-1996.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 96: 489-617.

• Henein, N. H. 1984. “Deux serrures d’époque romaine de la nécropole de Douch.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 84, 229-249.

• Hoskins, G. A. 1837. Visit to The Great Oasis of the Libyan Desert; with an Account, Ancient and Modern, of the Oasis of Amun, and the Other Oases Now Under the Dominion of the Pasha of Egypt. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman.

• Kiss, Z. 1980. “Un portrait d’impératrice à Douch (Kharga).” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 80: 31-34.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2013. “The Embroidered Tunic of Dush. A New Approach.” In Drawing Threads Together. Textiles and Footwear of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt. Proceedings of the 7th Conference of the Research Group ‘Textiles from the Nile Valley’, edited by A. De Moor and C. Fluck, 22-33. Tielt: Lannoo.

• Marthot, I. 2009. “Reddé (Michel), Douch III. Kysis. Fouilles de l’ifao à Douch. Oasis de Kharga (1985-1990), Le Caire, Institut français d’archéologie orientale, Documents de fouilles de l’Ifao 42, 2004.” Revue des études grecques 122/1: 219-221.

• Naumann, R. 1939. “Bauwerke der Oase Khargeh.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 8: 1-16.

• Nenna, M.-D. 2003. “Verreries de luxe de l’Antiquité tardive découvertes à Douch, Oasis de Kharga, Égypte.” In Annales du 15e congrès de l’Association internationale pour l’histoire du verre, 93-97. Nottingham: Association internationale pour l’histoire du verre.

• Nenna, M.-D. 2003. “De Douch (Oasis de Kharga) à Grand (Vosges): un disque en verre peint à représentations astrologiques.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d'archéologie orientale 103: 355-376.

• Reddé, M. 1991. “A l’ouest du Nil: une frontière sans soldats, des soldats sans frontière.” In Roman Frontier Studies 1989, edited by V. A. Maxfield and M. J. Dobson, 485-493. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

• Reddé, M. 1992. Le trésor de Douch (oasis de Kharga). Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Reddé, M. 1999a. “Un village dans les oasis d’Égypte: Douch.” In L’Afrique du Nord antique. Cultures et paysages, edited by J. Peyras, 67-84. Besançon: Presses universitaires franc-comtoises.

• Reddé, M. 1999b. “Sites militaires romains de l’oasis de Kharga.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 99: 377-396.

• Reddé, M. 2004a. Douch III. Kysis: Fouilles de l’Ifao à Douch, oasis de Kharga (1985-1990). Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Reddé, M. 2004b. “Des premiers voyageurs aux fouilles de l’Ifao.” In Douch III. Kysis: Fouilles de l’Ifao à Douch, oasis de Kharga (1985-1990), edited by M. Reddé, P. Ballet, A. Lemaire and C. Bonnet, 1-10. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Reddé, M. 2004c. “Les fouilles du village.” In Douch III. Kysis: Fouilles de l’Ifao à Douch, oasis de Kharga (1985-1990), edited by M. Reddé, P. Ballet, A. Lemaire and C. Bonnet, 25-74. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Reddé, M. 2007. “L’occupation militaire tardive dans les oasis d’Égypte. L’example de Douch.” In The Late Roman Army in the Near East From Diocletian to the Arab Conquest. Proceedings of a Colloquium Held at Potenza, Acerenza and Matera, Italy (May 2005), edited by A. S. Lewin and P. Pellegrini, 421-429. Oxford: Archaeopress.

• Reddé, M., P. Ballet, A. Lemaire and C. Bonnet. 2004. Kysis III. Fouilles de l’IFAO à Douch oasis de Kharga (1985-1990). Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Reddé, M., F. Dunand, R. Lichtenberg, J.-L. Heim and P. Ballet. 1990. “Quinze années de recherches françaises à Douch. Vers un premier bilan." Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 90: 281-301.

• Reiter, F. 2012. “A Remark on the Poll Tax Rate in Kysis.” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli and C. A. Hope, 327-330. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

• Sauneron, S. 1954. “Les temples de Khargeh et de Dakhleh.” Bulletin de la Société d'études historiques et géographiques del’Isthme de Suez 41: 73-89.

• Sauneron, S. 1955a. “Les temples gréco-romains de l'oasis de Khargeh.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 55: 23-31.

• Sauneron, S. 1955b. “Quelques sanctuaires égyptiens des oasis de Dakhleh et de Khargeh.” Cahiers d’histoire égyptienne 7: 279-296.

• Sauneron, S., D. Valbelle, P. Vernus, J.-P. Corteggiani, M. Vallogia, J. Gascou, G. Wagner and G. Roquet. 1978. “Douch. Rapport préliminaire de la campagne de fouilles 1976.“ Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 78: 1-33.

• Timm, S. ed. 1984-1992. Das christlich-koptische Ägypten in arabischer Zeit: Eine Sammlung christicher Stätten in Ägypten in arabischer Zeit unter Ausschluß von Alexandria, Kairo, des Apa-Mena-Klosters (Dēr Abū Mina), der Skētis (Wādi n-Naṭrūn) und der Sinai-Region. Vol. 3, 1480-1481. Wiesbaden: Dr Ludwig Reichert.

• Laroche-Traunecker, F. 2020. Le sanctuaire osirien de Douch: travaux dans le secteur du temple en pierre (1976-1994). Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Vernus, P. 1979. “Douch arraché aux sables.” Bulletin de la Société française d’égyptologie 85: 7-21.

• Wagner, G. 1981. “Les ostraca grecs de Douch.” In Proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Papyrology, New York, 24-31 July 1980, edited by R. S. Bagnall, G. M. Browne, A. E. Hanson and L. Koenen, 463-468. Chico, CA: Scholars Press.

• Wagner, G. 1986. “Le camp romain de Douch (Oasis de Khargeh, Egypte).” In Studien zu den Militärgrenzen Roms III: 13. Internationaler Limeskongress, Aalen 1983 : Vorträge, edited by C. Unz, 671-672. Stuttgart: Kommissionsverlag K. Theiss.

• Wagner, G. 1987. Les oasis d’Égypte à l’époque grecque, romaine et byzantine d’après les documents grecs: Recherches de papyrologie et d’épigraphie grecques. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Wagner, G. 1999. Les ostraca grecs de Douch (O. Douch) IV. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Wagner, G. 2001. Les ostraca grecs de Douch (O. Douch) V. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Wagner, G., F. Dunand, C. Roubert, F. Laroche-Traunecker, J.-C. Grenier and M. Rodjiewicz. 1983. “Douch: rapport préliminaire de la campagne de fouilles de l’automne 1981.” Annales du Service des antiquités de l’Égypte 69: 131-142.

• Wilkinson, J. G. 1843. Modern Egypt and Thebes. London: John Murray.

• Wuttmann, M. 2009. “Travaux de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 2008-2009.” Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale 109: 590-591, fig. 39.

Json data

Json data