MADĪNAT HĀBŪ (MEMNONEIA)

| Egyptian | Ḏmȝ | Tḏmȝʿ | Ḏmʿ | Ḏmȝ.t | Pr-Ḏmȝ | Pȝ-Ḏmȝ |

| Greek | τὰ Μεμνόνεια |

| Latin | Menonia |

| Coptic | jhme | qhmi |

| Arabic | مدينة هابو |

| English | Medinet Habu | Memnonea | Memnonia | Djeme | Jeme | Djema |

| French | Medinet Habou | Medinat Abu | Medinet Abou | Médinet Habou |

| DEChriM ID | 48 |

| Trismegistos GeoID | 1341 |

| Pleiades ID | 786067 | PAThs ID | 87 |

| Ancient name | Memnoneia |

| Modern name | Madīnat Hābū |

| Latitude | 25.719990863695134 |

| Longitude | 32.600480318069465 |

| Date from | 550 |

| Date to | 900 |

| Typology | Village |

| Dating criteria | - |

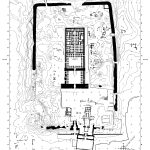

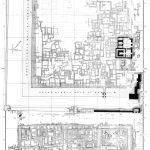

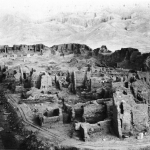

| Description | The site of Madīnat Hābū is situated on the west bank of the Nile on the outskirts of Luxor, at the foot of the Theban Hills. Today the site is best known for the monumental temple of Ramses III, but prior to the 19th century, the site also retained impressive material vestiges of the Late Roman and Coptic-periods, elements which have since been removed. We know, nonetheless, that Madīnat Hābū was home to a flourishing Christian community thanks to the plethora of texts which importantly associate the site with the famed Djeme (see: Stefanski and Lichtheim 1952). Not all of these texts are published. A small number of the Coptic ostraca were published by W. Till in 1938, while the remaining 400 were published by E. Stefanski and M. Lichtheim in 1952, though these were apparently less than half of the total retrieved, the remaining being “small and badly preserved fragments which are not worth publishing” (Stefanski and Lichtheim 1952: v). And a large number of the papyri were published by W. E. Crum and G. Steindorff in 1912- Whatsmore, four archaeologically attested churches(/chapels) further illuminate the situation at the site. The now-absent traces of Late Roman and Coptic-period life, which included domestic and religious structures, were concentrated in and around the temple of Ramses III, which was itself constructed atop of earlier structures belonging to the 18th Dynasty. Arguably the most significant of these Christian remains was a basilical church erected within the 2nd court of the temple which was removed by the antiquities service in 1891 prior to the commencement of restoration works (Hölscher 1934: 1, pl. 32; id 1954: 51-52, figs. 45, 57; Wilber 1940: 93; Timm 1984-1992: 1026). It has been posited that this was known as the “Holy Church of the Castrum Jeme”/“Holy Church of Jeme” referenced the texts, but there is no direct evidence to demonstrate this (Hölscher 1931: 56; id 1956: 51). Unlike the Pharaonic monument in which it was situated, the church never saw much scientific interest and so no floorplan was ever produced prior to its removal. Instead, our understanding of the structure and its architecture derives exclusively from drawings and photographs of the temple from the years prior (e.g., Granger 1745: 68), though a description of the baptismal font was offered by George Daressy at the beginning of the 20th century (Daressy 1920: 173). These various works demonstrate that it was a five-aisled basilica, and hypothetical floor plans have since been published (Hölscher 1954: 52-55, fig. 57). Grossmann tentatively considered the church to have been erected in the fifth century (Grossmann 2002: 457), though he had earlier posited a mid-6th century date (Grossmann 1991: 1497). Various modifications were necessary to the temple space to permit the erection of this church which, in addition to several graffiti, remain the only traces of its presence (Edgerton 1937: pls. 92-102). A much smaller church, and seemingly the earliest of the four churches recorded, is situated in the court of the temple complex of Eye and Haramhab (Hölscher 1954: 56, fig. 60; Timm 1984-1992: 1026). This church is understood to have developed out of a pre-existent structure the purpose of which is not clear; the excavators noted similarities with a small, covered marketplace, but considered this improbable given the structure’s presence on the edge of a cemetery. Wilber noted: “The excavators remark that it seems to have been built over a Roman bath”, but there appears to be no such reference (Wilber 1940: 93). Such a location could rather indicate that it was originally a private funerary mausoleum. The construction of the original building is considered to pre-date 300 based on the presence of later graves in and around the church which are dated to the fourth-fifth century, though exactly why the graves are situated in this time frame is not apparent (Hölscher 1954: 39-40, 56-57, figs. 60-61 and pl. 34). In addition to this was a small church situated outside the eastern fortified gate of the site, only a single course of which was preserved. Little information was published regarding this structure, but it is noted as being similar in plan to the basilica within the temple, albeit far more modest and apparently of a later date (Hölscher 1934: Pls. 9-10; id 1954: 55-56, fig. 59 and pl. 46; Grossmann 1991: 1497; Timm 1984-1992: 1026). It was suggested by the excavators that this could be the church of Apa Patermuthios mentioned in the papyri, but there is no reason given for this equivalence (Hölscher 1931: 56). Lastly, there is a church – or rather chapel – situated within a small temple in the northeast corner of the Madīnat Hābū enclosure which contains well-preserved paintings depicting the life and martyrdom of saint Menas (Wilber 1940; Hölscher 1931: 69; id 1954: 57; Timm 1984-1992: 1026). This is presumably the latest of the four churches, situated sometime in the 8th century (Wilber 1940: 101). Many of the Coptic-period houses were removed from the temple and surrounding areas presumably at the same time as the removal of the basilical church, with the few that remained subsequently being removed during the course of excavations in 1927. Only “the ruins outside the enclosure and on top of the old enclosure wall” were left in place (Hölscher 1954: 45). These structures had been in a remarkable state of preservation prior to removal, all comprising several stories. The best-preserved structures were those to the north and west of the temple, with a large collection of Roman-period structures to the north, dated by the excavators to the third-fourth century, a date aided by lamps as well as coins (Hölscher 1954: 37, 45, 67 and pl. 29; for a catalogue of the houses, see: p. 49-51 and pls. 40-44). |

| Archaeological research | Like the Pharaonic monuments at Luxor and Karnak, the temple of Ramses III has long-since attracted European visitors, as such, information pertaining to Madīnat Hābū has been recorded since at least the early 17th century. A brief overview of various visitors is offered in Timm (Timm 1984-1992: 1025), while Uvo Hölscher, in his introduction to the first volume, lists a variety of notable works of relevance, the earliest being those of Johann M. Wansleben (1677), Tourtechot de Granger (1745), and Frederic Ludvig Norden (1757 and 1792), accompanied by that of Wilkinson (1835: 41-76) and several others (Hölscher 1931: 1-2). The first “useful” ground plan was that of Richard Lepsius, who also prospected and dug “here and there” (Hölscher 1931: 1). In 1859, a certain M. Bonnefoy of the Service de conservation des monuments de l’Égypte began work at the site, though exactly what this entailed is not clear. After his death, work continued from 1860 until 1863 under the direction of M. Gabet until funds were depleted. The work was again picked up, this time by Georges Daressy, who apparently saw the work through to completion between 1888 to 1898/9. It is during this block of work that the basilical church was removed, in addition to several other areas being totally cleared down to the Ramesside level (e.g., Daressy 1926: 9-10). Very little information was published concerning this work, though there are several brief articles dedicated to individual finds (e.g., Daressy 1898: 74-76, 81-85, and 113-120; id 1899: 30-39; id 1900: 144-146; id 1908: 66-68; id 1911: 49-63; id 1920: 173), with a summary published once fieldwork had been completed (Daressy 1897). In 1909, Uvo Hölscher conducted a study of the Eastern Fortified Gate in preparation for a volume concerning the site, the publication of which instigated further digs at the behest of Gaston Maspero (Hölscher 1910). Consequently, excavations were conducted within the boundaries of Madīnat Hābū in 1912 under the direction of Theodore M. Davis, which seems to have continued only until 1913. As with the work at the end of the 19th century, this resulted in the removal of a large amount of material down to the Ramesside level with little record of the work conducted. This was followed by an expedition dedicated to epigraphic recording conducted by the Chicago Oriental Institute under the direction of Harold H. Nelson. After a preliminary survey of the existing buildings in 1927 by Hölscher, concession of the site was granted to the Institute resulting in the establishment of a team comprising the previously mentioned Epigraphic Section directed by Nelson and an Architectural Section directed by Hölscher, the former acting as field director for the whole project. This led to six seasons of work conducted between 1927 and 1933 and five publications dedicated to the excavation. |

• de Bock, W. 1901. Matériaux pour servir à I'archéologie de I'Egypte chrétienne, 85 n. 29. Saint Petersberg: Eugéne Thiele.

• Crum, W. E. and G. Steindorff. 1912. Koptische Rechtsurkunden des Achten Jahrhunderts aus Djeme (Theben). I. Band: Texte und Indices von W. E. Crum. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrich.

• Daressy, G. 1897. Notice explicatives des ruines de Médinet Habou. Cairo: Service des antiquités de l’Égypte.

• Daressy, G. 1898. “Listes géographiques de Médinet-Habou.” Recueil de travaux relatifs à le philologie et à l’archéologie égyptienne et assyriennes 20: 113-120.

• Daressy, G. 1899. “Listes géographiques de Médinet-Habou.” Recueil de travaux relatifs à le philologie et à l’archéologie égyptienne et assyriennes 21: 30-39.

• Daressy, G. 1900. “Comment fut introduit le naos du petit temple de Medinet-Habou.” Recueil de travaux relatifs à le philologie et à l’archéologie égyptienne et assyriennes 22: 144-146.

• Daressy, G. 1908. “Une nouvelle forme d’Amon. Annales du services des antiquités de l’Égypte 9: 66-68.

• Daressy, G. 1911. “Plaquettes émaillées de Médinet-Habou.” Annales du services des antiquités de l’Égypte 11: 49-63.

• Daressy, G. 1920. “Notes sur Louxor de la période romaine et copte.” Annales du service des antiquités de l’Égypte 19: 159-175.

• Daressy, G. 1926. “Le voyage d’inspection de M. Grébaut en 1889.” Annales du service des antiquités de l’Égypte 26: 1-22.

• Edgerton, W. F. 1937. Medinet Habu Graffiti Facsimiles. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

• Grossmann, P. 1991. “Medinet Habu.” In The Coptic Encyclopedia, vol. 5, edited by S. S. Attiya, 1496-1497. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

• Grossmann, P. 2002. Christliche Architektur in Ägypten, 455-457. Leiden: Brill.

• Hölscher, U. 1910. Das Hohe Tor von Medinet Habu. Eine baugeschichtliche Untersuchung. Leipzig: Otto Zeller.

• Hölscher, U. 1931. Medinet Habu Reports. I: The Epigraphic Survey 1928-31. II: The Architectural Survey 1929/30. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• Hölscher, U. 1934. The Excavation of Medinet Habu – Volume I. General Plans and Views. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• Hölscher, U. 1939. The Excavation of Medinet Habu – Volume II. The Temples of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• Hölscher, U. 1941. The Excavation of Medinet Habu – Volume III. The Mortuary Temple of Ramses III, Part I. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• Hölscher, U. 1951. The Excavation of Medinet Habu – Volume IV. The Mortuary Temple of Ramses III, Part II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• Hölscher, U. 1954. The Excavation of Medinet Habu – Volume V. Post Ramessid Remains. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• Stefanski, E. And M. Lichtheim. 1952. Coptic Ostraca from Medinet Habu. Chicago: The University of Chicago Oriental Publications.

• Till, W. 1938. “Koptische Schutzbriefe, miteinem rechtsgeschichtlichen Beitragvon H. Liebesny.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts Kairo 8: 71-146.

• Timm, S. ed. 1984-1992. Das Christliche-Koptische Ägypten in Arabischer Zeit: Eine Sammlung Christlicher Stätten in Ägypten in Arabischer Zeit unter Ausschyss von Alexandria, Kairo, des Apa-Mena-Klosters (Der Abu Mina), der Sketis (Wadi n-Natrun) und der Sinai-Region. Vol. 3, 1012-1034 (Gabal Šāma). Weisbaden: Dr Ludwig Reichert.

• Wilber, D. N. 1940. “The Coptic Frescoes of Saint Menas at Medinet Habu.” The Art Bulletin 22, 2: 86-103.

• Wilkinson, J. G. 1835. Topography of Thebes, and General View of Egypt, 41-76. London: John Murray.

Json data

Json data