DAYR UMM AL-ĠANĀʾIM

| Egyptian | Pȝ-sy (?) |

| Arabic | الدير | دير أم الغنائم | دير المنيرة |

| English | el-Deir | Deir el-Munira |

| DEChriM ID | 40 |

| Trismegistos GeoID | 14221 |

| Pleiades ID | 776167 | PAThs ID | - |

| Ancient name | - |

| Modern name | Dayr Umm al-Ġanāʾim |

| Latitude | 25.596300 |

| Longitude | 30.730395 |

| Date from | -700 |

| Date to | 450 |

| Typology | Military camp, temple |

| Dating criteria | Funerary, numismatic and ceramic material |

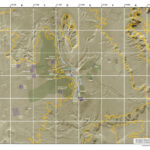

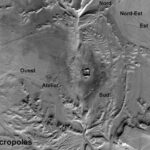

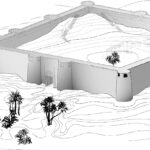

| Description | The site of el-Deir, also known as Dayr Umm al-Ġanāʾim, is located on the N-E edge of the Kharga Oasis, 25km N-E of the town of Madīnat al-Ḫāriǧa (Reddé 1999: 379; Dunand, Heim, Lichtenberg 2010: 13). It is situated on the Darb al-Rufūf, a route linking the oasis to Ğirğā and Faršūṭ, in the Nile Valley (Ghica 2012: 230). The site consists of an imposing fortress, a mud-brick temple dedicated to Amun of Hibis, a residential area dating to the Persian period, as well as five cemeteries. Occupation of the site seems to span from Prehistoric times until the fifth century CE (Bagnall & Tallet 2015: 4). Excavations have been ongoing since 1998 under the direction of Françoise Dunand, then under the direction of Gaëlle Tallet, in association with the University of Limoges. Research is currently funded by the French National Research Agency within the framework of the international CRISIS program. Fortress Temple Cemeteries In 2004, excavations began in the Western Necropolis, which has since been classified as ‘Christian’. The record of this cemetery includes various decorated textiles, a number of which are made from wool, a material rarely seen in ‘traditional’ funerary contexts (Dunand, Lichtenberg 2008: 276). The necropolis is somewhat cut into two independent sections, the northern and the southern half. The graves in the north are predominantly oriented E-W, while those in the south are oriented N-S (Dunand, Heim, Lichtenberg 2010: 42). It is this presence of woolen textiles, the E-W orientation of the graves, the single interments, as well as unique aspects of a number of mummies and representations of crosses that have led to the northern half being classified as a Christian cemetery (Dunand, Lichtenberg 2008: 276). This necropolis is consequently of particular importance in relation to the study of the evolution of funerary practices, particularly in relation to the spread of Christianity (Dunand, Lichtenberg 2008: 263, 274-275). It is understood to have been in use at least from the fourth century CE (Dunand, Lichtenberg 2008: 263, 276; Dunand, Heim, Lichtenberg 2010: 48). All of these chronological markers, if interpreted correctly, show that the site, or at least the cemeteries, have been in use for eight centuries, from at least the fourth century BCE, to the fourth/fifth centuries CE (Dunand, Heim, Lichtenberg 2010: 48). Embalmer’s workshop |

| Archaeological research | While not excavated until recently, the site has been known for some time, with the early investigations and descriptions centered mainly on the fortress (Dunand, Lichtenberg 2008: 261). The first mention of the site comes from Cailliaud in 1821, after his visit in 1818 (Cailliaud 1821: 96 & pl. 22, 2-3). This simple initiate description was followed by the earliest geological study conducted in the oases, that of John Ball at the end of the 19th century, then by the work of H. J. Llewellyn Beadnell as part of the Egypt Geological Survey. Additionally, the site was likely visited by members of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA), who conducted excavations in Kharga from 1908 to 1928, but no systematic exploration was ever undertaken. A number of objects in the MMA are believed to have originated from Umm al-Ġanāʾim, but their provenance has been lost (Heim, Lichtenberg 2010: 24). An area of the fortress was modified at the end of the 19th/beginning of the 20th century in order to house a small garrison of Egyptian soldiers (Dunand, Heim, Lichtenberg 2010: 22). The German scholar R. Naumann mentioned el-Deir in an article for MDAIK, which included a brief description and a plan of the fortress, whose walls were described as standing to a height of some 12 meters (Naumann 1939: 1-16 & fig. 1-7). Six decades later, a topographic survey of the site was then conducted by Ch. Braun and P. Deleuze, for which A. Lecler took photographs (Reddé 1999: 379). Eventually, excavations began on the site in 1998, led by Françoise Dunand (Dunand, Lichtenberg 2008: 9). Directorship was passed from Dunand to Gaëlle Tallet, and in 2010 a collaborative partnership was also initiated with the team from Amḥayda, led by Roger Bagnall. Since 2013, there has been an emphasis on restoration and development, and in 2014 the team’s architect Nicholas Warner has been engaged in a project geared towards restoring the fort in order to create a tourist-friendly site, while preserving the archaeological heritage (http://oasis.unilim.fr/patrimoine-oasien/). |

• Ball, J. 1900. Kharga Oasis: Its Topography and Geology. Cairo: National Printing Department.

• Bagnall, R. S. and G. Tallet. 2015. “Ostraka from Hibis in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Archaeology of the City of Hibis.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 196: 175-198.

• Beadnell H. LI. 1909. An Egyptian Oasis: An Account of the Oasis of Kharga in the Libyan Desert, with Special Reference to its History, Physical Geography, and Water-Supply. London: J. Murray.

• de Bock, W. 1901. Matériaux pour servir à l’archéologie de l’Égypte chrétienne, 1-6. Saint Petersberg: Eugéne Thiele.

• Bravard, J.-P., A. Mostafa, R. Garcier, G. Tallet and P. Ballet. 2016. “Rise and Fall of an Egyptian Oasis: Artesian Flow, Irrigation Souls and Historical Agricultural Development in El-Deir, Kharga Basic (Western Desert of Egypt).” Geoarchaeology 31, 6: 467-86.

• Brones, S. and C. Duvette. 2007. “Le fort d’el-Deir, oasis de Kharga. “État des lieux” architectural et archéologique.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 107: 5-41.

• Cailliaud, F. 1821. Voyage à l’oasis de Thèbes et dans les déserts situés à l’Orient et à l’Occident de la Thébaïde fait pendant les années 1815, 1816, 1817 et 1818. Paris: Imprimerie royale.

• Coquin, R.-G. 1991. “Monasteries of the Western Desert.” In The Coptic Encyclopedia, vol. 5, edited by A. S. Atiya, p. 1658b-1659a. New York: Macmillan.

• Coudert, M. 2013a. “The Christian Necropolis of el-Deir in the North Kharga Oasis.” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli and C. A. Hope, 451-458. Oxford: Oxbow.

• Coudert, M. 2013b. “Réflexion sur les pratiques funéraires coptes: l’exemple d’une nécropole de l’Antiquité tardive sur le site d’el-Deir dans l’oasis égyptienne de Kharga.” In Études coptes XII. Quatorzième journée d’études de l’Association française de coptologie, 11-13 juin 2009, université la Sapienza, Rome, 177-189. Paris: De Boccard.

• Coudert, M. 2014. “La nécropole byzantine du site d’el-Deir dans l’oasis de Kharga en Égypte. Étude de cas: l’individu W99.” In Le Myrte et la rose. Mélanges offerts à Françoise Dunand par ses élèves, collègues et amis, edited by G. Tallet and C. Zivie-Coche, 249-258. Montpellier: Presses universitaires de Montpellier.

• Coudert, M. 2015. “La nécropole de l’Antiquité tardive du site d’el-Deir dans l’oasis de Kharga. Étude des pratiques funéraires coptes.” Thesis, University Paris IV-Sorbonne, Paris.

• Dunand, F. 2004. “Le mobilier funéraire des tombes d’el Deir (oasis de Kharga): témoignage d’une diversité culturelle?” Städel-Jahrbuch, Sonderdruck, Neue Folge 19: 565-579

• Dunand, F. and M. Coudert. 2014. “Les débuts de la christianisation dans les oasis. Le cas de Kharga.” In Alexandrie la divine, edited by C. Méla and F. Möri, p. 796-801. Geneva: La Baconnière.

• Dunand, F., M. Coudert and F. Letellier-Willemin. 2008. “Découverte d’une nécropole chrétienne sur le site d’el-Deir (oasis de Kharga).” In Études coptes X, Douzième journée d’études (Lyon, 19-21 Mai 2005), edited by A. Boudhors and C. Louis, 137-35. Paris: De Boccard.

• Dunand, F., J.-L. Heim, and R. Lichtenberg. eds. 2010. El-Deir nécropoles I: la nécropole Sud. Paris: Librairie Cybèle.

• Dunand, F., J.-L. Heim, and R. Lichtenberg. eds. 2012a. El-Deir nécropoles II: les nécropoles Nord et Nord-Est. Paris: Librairie Cybèle.

• Dunand, F., J.-L. Heim, and R. Lichtenberg. 2012b. “Les nécropoles d’el-Deir (oasis de Kharga).” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli and C. A. Hope, 279-296. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

• Dunand, F., J.-L. Heim, and R. Lichtenberg. eds. 2015. El-Deir nécropoles III: la nécropole Est et le piton aux chiens. Paris: Librairie Cybèle.

• Dunand, F. and R. Lichtenberg. 2005. “Des chiens momifiés à el-Deir, Oasis de Kharga.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 105: 75-87.

• Dunand, F. and R. Lichtenberg. 2008. “Dix ans d’exploration des nécropoles d’el-Deir (oasis de Kharga). Un premier bilan.” Chronique d’Égypte 83: 258-88.

• Dunand, F., R. Lichtenberg, C. Callou and F. Letellier-Willemin. 2017. El-Deir nécropoles IV: les chiens momifiés d’El-Deir. Paris: Librairie Cybèle.

• Dunand, F. and R. Lichtenberg. 2019. “Des réfractaires à l’enrôlement ? Plusieurs cas d’automutilation dans une nécropole égyptienne.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 119: 115-123.

• Dunand, F., G. Tallet and F. Letellier-Willemin. 2005. “Un linceul peint de la Nécropole d'El-Deir, oasis de Kharga.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archeologie orientale 105: 89-101.

• El-Deir Oasis. 2020. http://oasis.unilim.fr/accueil/

• Ghica, V. 2012. “Pour une histoire du christianisme dans le désert Occidental d’Égypte.” Journal des savants 2: 189-280.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2010a. “Les textiles.” In El-Deir nécropoles I: la nécropole Sud, edited by F. Dunand, J.-L. Heim, and R. Lichtenberg, 191-222: Paris: Librairie Cybèle.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2010b. “Quatre écharpes de la nécropole chrétienne d’El-Deir, oasis de Kharga.” In Études coptes XI: treizième journée d'études (Marseille, 7-9 juin 2007), edited by A. Boud'hors and C. Louis, 151-160. Paris: De Boccard.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2011. “Accessories from the Christian Cemetery of El Deir.” In Dress Accessories of the 1st Millennium AD From Egypt: Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the Research Group ‘Textiles from the Nile Valley’, Antwerp, 2-3 October 2009, edited by A. De Moor and C. Fluck, 96-109. Tielt: Lannoo.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2012a. “Contribution of Textiles as Archaeological Artefacts to the Study of the Christian Cemetery of el-Dier.” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli and C. A. Hope, 491-499. Oxford: Oxbow.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2012b. “Les textiles.” In El-Deir nécropoles II: les nécropoles Nord et Nord-Est, edited by F. Dunand, J.-L. Heim and R. Lichtenberg, 385-402. Paris: Librairie Cybèle.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2013. “A Long and Narrow Sleeved Tunic of the Mummy W14.” In Textiles, Tools and Techniques: Proceedings of the Eighth Conference of the Research Group “Textiles from the Nile Valley.” Antwerp 5th-6th October 2013, edited by A. De Moor and C. Fluck, 26-37. Tielt: Lannoo.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2014a. “Les décors de jour d’El-Deir: une machine à remonter le temps dans l’oasis de Kharga.” In Le myrte et la rose. Mélanges offerts à Françoise Dunand par ses élèves, collègues et amis, edited by G. Tallet and C. Zivie-Coche, 371-83. Montpellier: Presses universitaires de Montpellier.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2014b. “A Sheepskin with Its Wool from the Christian Cemetery of El-Deir, in the Oasis of Kharga, Egyptian Western Desert.” In Fourth Conference of Purpurea Vestes 5th-6th November 2010, edited by C. Alfaro, M. Tellenbavh and J. Ortiz, 49-56. Valencia: University of Valencia.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. 2020. “Tackling the Technical History of the Textiles of El-Deir, Kharga Oasis, the Western Desert of Egypt.” In Egyptian Textiles and Their Production: ‘Word’ and ‘Object’ (Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods), edited by Maria Mossakowska-Gaubert, 37-49. Lincoln, Nebraska: Zea Books.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. Forthcoming. “Le linceul du nouveau-né de la tombe 35, de la nécropole chrétienne d’El-Deir, Oasis de Kharga, Égypte”. In Le commerce des textiles (tissus, dentelles, tapisseries…), 23ème assemblée générale du Centre international d’étude des textiles anciens, Bruxelles 28 septembre-1er octobre 2009.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. and F. Médard. 2012. “Techniques inattendues dans un fragment textile en coton du site d’El-Deir, oasis de Kharga, désert Occidental égyptien.” Archaeological Textiles Review 54: 62-71.

• Letellier-Willemin, F. and C. Moulherat. 2006. “La découverte de coton dans une nécropole du site d’el-Deir, oasis de Kharga, désert Occidental égyptien.” Archaeological Textiles Newsletter 43: 20-26.

• Maspero, J. 1912. Organisation militaire de l’Égypte byzantine. Paris: Honoré Champion.

• Meinardus O. F. A. 1965. Christian Egypt, Ancient and Modern. Cairo: Cahiers d'histoire égyptienne.

• Naumann, R. 1939. “Bauwerke der Oase Khargeh.” Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 8: 1-16 and fig. 1-7.

• Reddé, M. 1999. “Sites militaires romains de l’oasis de Kharga.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 99: 377-396.

• Tallet, G. 2012. “Les cartonnages.” In El-Deir nécropoles II: les nécropoles Nord et Nord-Est, edited by F. Dunand, J.-L. Heim and R. Lichtenberg 227-90. Paris: Librairie Cybèle.

• Tallet, G. 2014. “Culture matérielle et appartenances ethniques: quelques questions posées par les nécropoles d’El-Deir (oasis de Kharga, Égypte).” In Dialogues d’histoire ancienne supplément 10, 219-255.

• Tallet, G., J.-P. Bravard and R. Garcier. 2011. “L’eau perdue d’une micro-oasis. Premiers résultats d’une prospection archéologique et géoarchéologique du système d’irrigation d’El-Deir, oasis de Kharga (Égypte).” In Histoire des réseaux d’eau courante dans l’Antiquité – réparations, modifications, réutilisations, abandon, récuperation, edited by C. Abadie-Reynal, S. Provost and P. Vipard, 173-88. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

• Tallet, G., Gradel, C., and F. Letellier-Willemin. 2012. “Une laine bien plus belle et plus douce que celle des moutons à El-Deir, oasis de Kharga, désert Occidental égyptien.” In Entre Afrique et Égypte: Relations et échanges entre les espaces du sud de la Méditerranée à l’époque romaine, edited by S. Guédon, 119-41. Bordeaux: Ausonius.

• Tallet, G., C. Gradel, and S. Guédon. 2012. “Le site d’El-Deir, à la croisée des routes du desert Occidental: nouvelles perspectives sur l’implantation dee l’armée romaine dans le desert égyptien.” In Grecs et Romains en Égypte. Territoires, espaces de la vie et de la mort, objets de prestige et du quotidien. Actes du Colloque international de la SFAC, Paris, 15 novembre 2007, edited by P. Ballet, 75-92. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

• Tallet, G., J.-P. Bravard, R. Garcier, S. Guédon and A. Mostapha. 2012. “The Survey Project at El-Deir, Kharga Oasis: First Results, New Hypothesis.” In The Oasis Papers 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis Project, edited by R. S. Bagnall, P. Davoli and C. A. Hope, 349-361. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

• Wagner, G. 1987. Les oasis d’Égypte à l’époque grecque, romaine et byzantine d’après les documents grecs: Recherches de papyrologie et d’épigraphie grecques, 170, 406. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

• Wagner, G. 1991. “Al-Dayr.” In The Coptic Encyclopedia, vol. 3, edited by A. S. Atiya, 695. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Json data

Json data